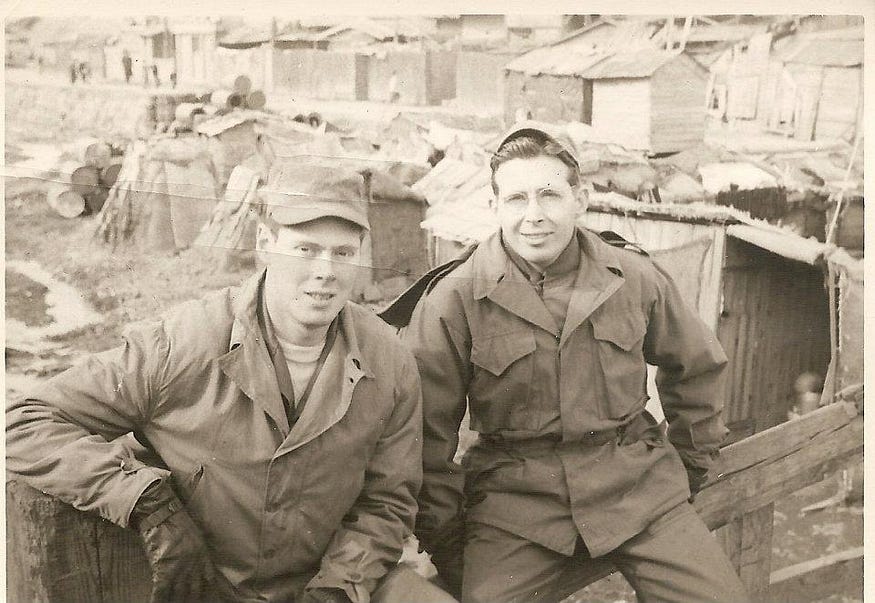

For Memorial Day, in honor of my father, I’m sharing this article I wrote a few years ago about his military service in Korea and his Honor Flight experience with a Northern Illinois vets’ group. At the end of this article is a video of the Honor Guard service at his funeral in February.

Dad’s first homecoming as a war veteran was in March 1953, two years to the month after he was drafted into the army for the Korean War. He arrived home to the U.S. at Seattle, to a port with a small crowd of civilians and a sign reading “Welcome Home Defenders of Freedom.” He’d been overseas since September 1951, entirely in Korea except for two weeks extra training at a naval academy at Etajima, Japan.

From Seattle, Dad traveled with other returning soldiers by Pullman train to Camp Carson in Colorado Springs. The Pullman was a step up from the slow-moving, no-sleeper troop train he’d rode when he was inducted in Chicago and sent to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, in 1951—a step up in comfort, at least, if not in service. Soldiers were entitled to a free dinner on Pullmans, which didn’t please the porters working for tips. “If you want your dessert, put some money on the table,” the porters told the soldiers. “If we don’t see any money, you don’t see any dessert.”

After nine days at Camp Carson, Dad finally made it back to Chicago. He wanted to get home soon as he arrived, but my grandmother had other ideas. Proud of her only son and happy to have him back healthy and whole, she and my grandfather and my aunt June (my dad’s only sibling) headed to the lakefront to take pictures with my dad still in his uniform. My grandparents and aunt were in winter coats (March in Chicago demands them), but my dad had only the lightweight Eisenhower jacket he’d been given by the army. When my dad sees those pictures today, what he remembers most is the wind and cold coming off Lake Michigan that day.

Perhaps the cold winter welcome home was only fitting—the war in Korea was one of the first major conflicts of the Cold War, after all, and a cold war was what soldiers in Korea found themselves literally engaged in, battling through an especially harsh and deadly winter in 1950–51. My dad’s service was in the second and third winters of the war, and he was farther south in the fighting zone, in lower mountainous areas than the first winter’s troops. Still, he spent his first winter sleeping in a Quonset hut, the second sleeping on a cot on the floor of an abandoned schoolhouse. Of the two, he preferred the Quonset hut. It was drafty, but it kept in the body heat better and made the freezing nights a little more tolerable.

Thankfully, Dad’s second homecoming as a war veteran was in warmer days—in August 2015. He had a bigger crowd too—including his wife, six children, and several grandchildren—and a full motorized escort in the form of a bikers’ club all the way back to Chicago from Milwaukee Airport. This time around, the homecoming was from Washington, DC, where my dad went with 45 other veterans on an Honor Flight organized by the Veterans Network Committee of Northern Illinois. Dad was part of a group representing veterans of World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War and from all four branches of military service—Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines, as well as the Women’s Army Corps. There were three women veterans, including a former “Rosie the Riveter” bomber aircraft worker, and one father-and-son duo, a man who’d served in WWII making the trip with his Vietnam veteran son. The veterans ranged in age from 65 to 96. Their Honor Flight trip lasted three days, and less than three weeks after their return, one of the group would pass away. This is the story of their Honor Flight and homecoming.

Dad first heard about the Honor Flight program in 2011, when a friend and former coworker of his signed up in Chicago. Harold, my father’s friend, was 92 and a WWII vet who spent the last months of the war as a POW in a German stalag. More than 60 years later, Harold still carried bullets from enemy machine-gun fire in his back, a “souvenir” of his service that had caused a lifetime of health problems. His Honor Flight was a one-day trip, the standard length of most Honor Flights. He was accompanied by his daughter, who served as his guardian (usually a family member or friend assigned to the traveling veteran to help him or her during the trip). After the trip, Harold didn’t live long enough to tell much about it—he died the day after his return. His story, though, was covered by a few local news outlets, and my dad was impressed by what the experience had meant to Harold’s family.

In 2013, Dad finally applied for his Honor Flight with the same hub Harold had gone through. But Dad did not serve in WWII, and despite his age (he was born in 1928) he was waitlisted. The hub he’d applied with has made WWII vets their first priority, and until all vets from that war have gotten their chance for an Honor Flight, Korea and Vietnam vets remain on a waitlist, with the exception of any who are terminally ill.

This is standard policy with many of the 130-plus Honor Flights throughout the U.S. The network’s founding mission was to transport aging WWII vets to DC to see the National World War II Memorial, which opened to the public in 2004. The first Honor Flights were made in May the following year, when Earl Morse, an Ohio-based veterans’ physician and former Air Force captain, offered to personally escort a number of his patients to see their new memorial before failing health made it impossible. Then in 2006, Jeff Miller, a North Carolina dry-cleaning businessman whose father and uncle had served in WWII, began an organization called Honor Air that borrowed from Morse’s idea but figured out how to use commercial airlines to escort the veterans and fund their trips. By 2007 Morse and Miller had merged their programs to form the Honor Flight Network.

Since that first Honor Flight in 2005, the network has brought over 145,000 veterans to their national war memorials. James McLaughlin, current chairman of the network, says in 2014 alone over 21,000 vets and over 18,000 guardians visited DC. With an estimated 514 WWII vets dying each day according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the focus remains on bringing veterans from that war to their memorial. But with Korean War vets reaching their 80s and even 90s, some hubs have begun opening up applications from veterans of Korea and Vietnam. A few hubs have even sprung up that are reaching out exclusively to Korean or Vietnam War vets (as well as hubs exclusively for women veterans). On my father’s Honor Flight, there were 23 Korean War vets—the largest group out of the three wars represented. Meanwhile, three of the eight Vietnam veterans on the trip were already in their 70s.

This wasn’t the first time the Veterans Network Committee of Northern Illinois, the hub my father finally went through, took Korean and Vietnam War veterans on its Honor Flight. An official Honor Flight hub since 2010, the Veterans Network Committee (VNC) opened up its trips to post-WWII vets in 2014. One of the vets on that trip was a terminally ill Vietnam vet, but the committee’s founder and president, Randy Granath, reckoned it was time to open up to Korean and Vietnam War vets anyway. After this year’s VNC Honor Flight, when I asked Granath about the limitations some hubs still impose, he brought up the fact of people getting cancer in their 50s or dying of a heart attack in their 40s. “Who are we to say who can’t go?” he says, adding that he hopes to keep doing this long enough to include Gulf War vets on the VNC Honor Flights.

Granath is a Vietnam vet who’d been active in veterans groups in the 1980s. He wasn’t planning on becoming involved with a veterans organization again in more recent years, until his son, Kyle, entered the military. Kyle had been in the ROTC at Ball State University in Indiana when 9/11 happened. He was called to active duty in 2002, ultimately serving nine years in the military and completing five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan. While Kyle was in the service, Randy and his wife, Pattie, became frustrated with the lack of support and resources for current service members and their families and with what they felt was a gap between the civilian community and veterans. Eventually the Granaths decided to build a new local veterans group, and the Veterans Network Committee of Northern Illinois was born, with five initial members, in March 2010.

Headquartered in Cary, a town about 45 miles northwest of Chicago, today the VNC is a full veterans organization with 140 members and 13 programs offering assistance to veterans and their families, one of which just happens to be the Honor Flights. Its other programs include support groups for veterans, food deliveries and assistance to homeless or disabled vets, care packages for overseas military, and a Memorial Day “Field of Honor” display in which more than 325 U.S. flags are planted in public sites around Cary to commemorate the Illinois soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. As a vets’ organization, the VNC is unique in that nonveterans are welcomed as charter members. It’s a way to create awareness and promote community involvement by including people who may not have served in the military themselves but who still have “skin in the game,” as Randy calls it—such as the parents or spouses of soldiers on active duty or the children of war veterans. Granath describes the VNC’s structure as like an accordion, gesturing as if he’s holding one in his hands. “We have the Honor Flights for the older vets on the one end and the Field of Honor for the younger generation on the other end, and they function like bookends and bring in all the rest of the programs together.”

The Honor Flight, however, is definitely the VNC’s most time-consuming program, requiring at least six months’ preparation, from the fundraising that begins in March to the actual trip in August. The VNC’s Honor Flight is a 3-day trip, rather than the standard 1-day event of most other hubs. While this limits the VNC to only one Honor Flight a year, Granath points out there’s more time for the veterans to get to know each other on their trip and bond over shared experiences. Granath doesn’t come out and say it, but there’s a clear therapeutic element to the VNC’s version of an Honor Flight. Not just a way for old veterans to see their war memorials or for civilian Americans to say thank you to veterans, the VNC’s Honor Flight allows for whatever emotional needs the veterans may be seeking to be met—whether that’s bonding or respect, validation or closure. And it’s an element that becomes even more apparent during the homecoming portion of the VNC’s Honor Flight.

What Dad wanted from his Honor Flight was a chance to see some of the memorials in DC. He had donated to the fund for the Korean War Veterans Memorial back before it was built but had yet to see it since it opened in 1995. He was in his 60s when the memorial was being built—he’s in his 80s now and suffered a heart attack in the time between. Until he got accepted for the VNC’s 2015 Honor Flight, he was still being waitlisted at the original hub he applied with back in 2013, and he only heard about the VNC Northern Illinois hub through a chance conversation with the VNC Honor Flight cochair at the local American Legion.

One of his first actions after getting accepted was picking a guardian. He chose his eldest son, Dan. There are six children in our family, and of course any one of us would’ve loved to have gone with him. But Dan happened to be there when Dad got word of his acceptance, so he got the job of guardian. Dan has no military experience, nor have the rest of us in the family. Dan grew up during the Vietnam War, but the draft ended shortly before he turned 16 and mandatory Selective Service registration ended nine days after he turned 18 in March 1975. (The war ended another month later, on April 30.)

No one in our family since has come as close to military service, mandatory or voluntary. But for a few generations we had a run of warriors in our lineage, a family tradition of “skin in the game” that we know goes as far back as the Civil War, when a great-grandfather of my mother’s served on the Union side. A 40-something emigrant from Ireland, he likely signed up for the cash bounty that enlistees were offered during that war. In World War I my maternal grandmother’s cousin was killed in France only 11 days before the Armistice. My paternal grandfather, who’d emigrated to the U.S. from Norway as a child, also fought in World War I. He was drafted, yet as a foreign-born citizen he was also required to sign a loyalty pledge to the U.S. In World War II one of my uncles was drafted into the Navy and another uncle enlisted in the Army at age 17 at the end of the war. The latter uncle, Daryl, was still in the service and stationed in Germany when the U.S. entered the Korean War. He was sent immediately to the front lines in Korea where he served as a rifleman and endured that first brutal winter of the war, a winter so cold that dead soldiers were routinely stripped of their cold-weather gear by opposing forces.

This uncle never spoke of his war experiences—until 9/11 and the run-up to the war in Iraq, when all the talk of war and terror in the news must have finally brought up some long-buried memories and emotions. As the U.S. was gearing up for war, he had a rare conversation about Korea with my father one night, where he admitted, in the understated way of Midwesterners and men of the Greatest Generation, that he’d been terrified when he got to Korea (“At first I was afraid I’d turn chicken…but I guess I made it through alright.”). The conversation turned to Iraq and my usually conservative uncle surprised my liberal father by strongly objecting (as my father did) to President Bush’s call to war. It wasn’t right to be sending our young people there. It wasn’t going to do anything but put them in harm’s way.

After the conversation, my aunt and mother—both of whom had been listening quietly—were a bit mystified as to what made my uncle start speaking so much about Korea so suddenly. In 50 years of marriage this was the most my aunt (who’d met my uncle at a USO right after his return from Korea) had ever heard him talk about the war. Later that night he had a nightmare of some sort that awakened and physically distressed him to the point of breaking out in a heavy sweat and requiring a trip to the hospital and made him momentarily confused about what year it was and even who and where he was. This was also a first.

Despite the Honor Flight Network’s original mission of getting all WWII vets to their DC memorial, neither of my uncles, though still alive, is able to go on an Honor Flight. Lloyd, my Navy uncle, is literally bent over in half by Parkinson’s, and Daryl currently undergoes kidney dialysis three times a week. I don’t know if they’d want to go even if they could. Perhaps they would, perhaps not. As I’ve learned from my dad as he’s mentioned other veteran friends of his, some veterans simply aren’t interested. Maybe they don’t want to revisit the past, or maybe they don’t like to travel. Or maybe they don’t want to deal with another lengthy application. To go on an Honor Flight, both veterans and their chosen guardians are required to fill out extensive paperwork, covering everything from medical history and needs to travel identification clearance. The VNC’s application arranges for the veterans to get TSA clearance ahead of the trip to save time and help things run more smoothly at the airport, which Granath says often results in some comical misunderstandings. Instead of supplying an official photo ID for TSA purposes (as explicitly requested in the application), the vets will turn in sentimental shots of themselves from their last vacation or their grandkid’s wedding.

As the date of the Honor Flight nears, there are orientations for the vets and their guardians, and family members are asked to write letters and cards for their veteran, which is unbeknownst to the veterans themselves. As the family, all we’re told is that at some point on the trip the veterans will be presented with our letters and cards, something like in their service days when the mail arrived with cherished letters from home. For some reason the idea of a veteran with no family not getting any mail worries my mother. (I chalk this up to her own childhood wartime memories. She had a sister who spent World War II writing to soldiers overseas and collecting their photos, something like the Marty Maraschino character in “Grease.”)

When the first day of the Honor Flight finally comes, Dad and Dan head out early to a local school where all the veterans, guardians, and VNC volunteers are gathered to make their way to Milwaukee Airport by coach bus. Milwaukee Airport is about an hour away, but it’s something of a calmer leaving point than the Chicago O’Hare and Midway airports. Considering there are 46 veterans, 46 guardians, plus volunteers and VNC members, as well as a wheelchair for each veteran (for health and insurance reasons, regardless of whether the veteran has mobility difficulties), the smoother the check-in and boarding process can be, the better. The group will be flying into Baltimore and checking into a hotel with a group dinner in the evening. It’s at these airport procedures, both in Milwaukee and Baltimore, where the veterans start to experience their first surprises, their first public gifts of appreciation and honor. At the airports are active military members and glee clubs who applaud and cheer on the veterans as they wait for their flights. (“It was kind of embarrassing,” Dad says later of all the unexpected attention. But my brother laughs and says, “Yeah, Dad was holding his hands out on both sides giving everyone high-fives, the whole time I was pushing him.”)

Their next day is a full one visiting up to 11 memorials in DC. Along with the memorials dedicated to the veterans of WWII, Korea, and Vietnam are memorials to the Navy and Air Force, the battle at Iwo Jima, and women in the military. They also visit the Lincoln Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery to see the changing of the guard. Each memorial has been included on this trip because each has its own meaning to every veteran. There are three women veterans in this group—a member of the WWII Women’s Army Corps, a woman who worked on aircraft bombers during WWII à la Rosie the Riveter, and a Marine who served in Vietnam. At the Women in Military Service for America Memorial, there’s a chance for the women to register their experiences and draw up their service records on a computer. When one of the women, Rose of the Women’s Army Corps, draws up her record, complete with a photo of her younger self in uniform, a volunteer puts it on a giant screen for everyone in the room to see. In pictures from that day, Rose beams alongside her record of service, looks thoughtfully at the image of her 1940s self, and sits patiently under the giant screen as the other vets and guardians and volunteers take her photo. At the Korean War Veterans Memorial my dad gathers for a group photo with the other Korean War vets around the stainless steel soldiers in the center of the memorial. In the pictures, the pale green statues appear nearly bleached white by the midday sunlight, and it looks nothing like the kind of weather my father and the other vets of Korea remember.

It’s such a full day for the veterans and their guardians, back home we don’t get many updates other than the occasional text or photo from my brother. After their memorial visits, they have another group dinner ahead of them on their second night. Meanwhile, we’re preparing for the homecoming for the next day, making signs and planting little American flags around the house and yard. On the third day of the trip, the group is scheduled to get back to the Chicago area around noon, and the families are to head over late morning to the local school where everyone gathered the first day of the trip.

It’s on this last morning, on the flight back to Milwaukee, when the veterans get mail call. The VNC volunteers walk up and down the aisles of the plane delivering packages to the vets—for each, an envelope filled with letters and cards. My dad’s envelope is stuffed with letters from my mother and all his children and grandchildren, as well as cards from schoolchildren who’d been asked to write the veterans so that every vet has something, everyone gets mail. For my father there are drawings of rainbows and blue houses and even a detailed depiction of one child’s classroom, with messages like “I hope you are having a little fun!” addressed to “Dear Vetaren.” On the plane my brother sits next to my dad as he quietly reads his mail. Afterward Dan will tell us Dad became visibly emotional while going through all his letters, more than at any other time on the trip.

Back home the rest of our family arrives at the school for the homecoming ceremony. The school entrance is lined with flags—national, state, military, POW/MIA. There are elderly color guard soldiers gathered near the curb and teenage naval cadets huddled beside the side door, and a few pre-teen scouts weaving through it all. Inside the school the auditorium is set up with a few hundred folding chairs, more flags and bunting, donated food and drinks, and a long table at the back with information about the VNC and the Honor Flight Network. At the front of the auditorium, a big band plays Glenn Miller and other swing-era oldies, with a few recent-ish selections from the Blues Brothers (no, we are not in Chicago city limits, but we’re close enough).

The mood is festive and Fourth of July-ish. My family and I sit on some lower bleachers as updates from Dan come in about their journey from Milwaukee Airport. I recognize a couple faces from the local American Legion and note a number of exceptionally calm, golden-coated dogs wearing camouflage vests and American flag bandannas around their necks. These are comfort dogs, raised and trained by veterans to serve and help other veterans at home or at VFWs, VA hospitals, or trauma care centers and such. Each dog has a veteran owner, and when one of them catches me trying to take a quick photo of his dog, he hands me a little trading card of sorts. I look at the card and see a puppy version of the dog in the arms of the same man talking to me. Underneath is a pet’s name (Blitz) and a human name (Bob). “He’s named after a military dog from Vietnam, one of the K9s. All the dogs are,” says Bob, who also served in Vietnam. One of the other men hands me his card, and before I know it I have four comfort dog trading cards.

We get word from my brother sooner than we expect that the VNC buses are only a few minutes away. He mentions they have an escort, but none of us realize what that means until they arrive. Everyone has gathered outside and lined up along the curb when a rumbling is heard and begins to grow louder. There are sirens too—police escort vehicles—but it’s the rumbling that takes over the neighborhood. Suddenly an army of motorcycles swings around the corner, growling past us for a good few minutes. Some of the bikers have a person on their backseat or riding shotgun, and I’m momentarily confused and worried in thinking these are the elderly Honor Flight veterans. But finally two coach buses come around the corner, to much cheering and applause, before parking in front of the school entrance.

The veterans are let off one by one. Each one gets a walk or wheelchair-escort of honor with his or her guardian up the pathway into the school, passing all the families and cadets and color guard soldiers and the line-up of flags and homemade welcome-home signs. This is the point when it becomes hard not to be affected by this event. For most of us there, this is the first time we get to see all the other veterans besides our own. Some of them are very frail, some cannot sit up straight anymore, a few salute with a visible hand tremor, most smile and wave, and a couple look unexpectedly overcome by the welcome home, their caps pulled low to cover the emotion in their eyes. My dad does not spot us in the crowd as he makes his entrance. He salutes the color guard and the cadets, and my brother smiles big behind him. Dad is wearing a Korean War vet cap and has sunglasses on, so it’s a little hard to see his face and reaction, but we, his family, can see he is fighting back tears. We’ve known his face all our lives, so we just know.

Back inside the auditorium, the vets sit up on the stage facing all the audience. It takes a while for everyone to calm down—so many families keep running up to their fathers and mothers and grandparents there on the stage, as if they haven’t seen them in years and can’t stand to be separated from them much longer. I have a memory of a picture I saw in a school textbook when I was a teenager, of a young woman running across a tarmac to greet her father upon his return from Vietnam. It seems a silly comparison to make now, since these war veterans have been gone only three days—but the picture flashes in my brain anyway, for the first time with an emotion I can feel along with it.

The crowd eventually situates itself and settles down, and soon there are songs and speeches by Randy Granath and the other VNC organizers and the mayor. The guardians have joined the rest of us among the folding chairs and bleachers, and as each veteran is introduced on stage, my brother supplies information here and there, pointing out which guys our dad bonded with the most and telling us about the father-and-son veterans on the trip. The oldest of the group is a WWII vet named Walter, his son Ben is a Vietnam veteran. One lives in northern Illinois, the other in Colorado. But the VNC arranged it so they could do the Honor Flight together, each with his own guardian.

In between the speeches and commentary, the veterans are presented with gifts. This year, for the first time for the VNC, a group of women quilters in Huntley, Illinois, have made a quilt for each veteran. The Quilts of Valor project began in Delaware in 2003 by a former Peace Corps worker and nurse-midwife whose son was deployed to Iraq. The project spread to Huntley in 2011, when the Gazebo Quilters Guild began making quilts for local amputees who’d served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Each quilt is unique with an entirely hand-stitched front, taking over 100 hours of individual labor, and the names of the women who worked on the quilt sewed into its bottom corner with a message of gratitude. They’ve even made one for Randy, the founding organizer, a father of a veteran, and a veteran himself. And Randy returns their favor by taking his quilt and wrapping it around his body, modeling the women’s arduous and beautiful work for everyone in the auditorium.

Next the veterans get another gift from the motorcycle crew, and we finally learn who these bikers who brought the veterans all the way nonstop from Milwaukee to Chicago are. The Warriors Watch Riders are a group of motorcycle enthusiasts, many of them also war veterans, with local crews who provide escorts for military events such as homecomings, funerals, and Honor Flights. They look like you’d expect a group of bikers to look—leather-clad, tough and tattooed—so it’s all the more touching to see them approach each of these old veterans with respect and a sense of protectiveness. They present each veteran with a coin with military and motorcycle symbols on it and a striking message: “Never again will an American warrior be scorned or ignored.”

After the homecoming, rather than rumbling off right away, the bikers stick around to shake the hands of the veterans, giving each one personal thanks for their service. All the families mill around the auditorium and the school entrances, taking pictures or thanking the VNC volunteers and meeting the new buddies their veteran made on the trip. In the meantime, the big band has hit it up again and a few folks show off their swing moves at the front of the auditorium. With Dad, my family returns to my parents’ home, with its front yard decorated with flags and welcome-home signs, and we spend the rest of the afternoon hearing about the trip and eating homemade chocolate cupcakes topped with American flag picks.

In the days and weeks to come, there are a lot of memories of the trip to sort through for my dad. So many pictures and videos, cards and letters, and questions and congratulations from those of us who stayed home. I live with my parents and help my dad edit his pictures and order print-outs from the local drugstore. Eventually I meet with Randy Granath to hear more about the VNC and the Honor Flights. The homecoming celebration is what sticks in my mind the most—perhaps because that was the only part of the experience I and the rest of my family were a part of, but also because of all the work that went into it. I was struck most by what incongruous groups the homecoming brought together: therapy dogs, a ladies’ quilting club, a biker gang. Yet undeniably they all share an underlying purpose of not only respect for war veterans but also comfort and protection. Before the homecoming I’d been expecting more jingoism at the event, and though there were American flags all over the place (as well as all over our front yard) and there was a singing of the national anthem of course, there was more attention to the kind of healing this entire event could bring to veterans than I’d anticipated. And cutting through all the celebration and bunting and big band tunes was a clear demonstration of what the community can do to contribute to our veterans’ healing, of how the gap between the civilian community and the military and veteran communities might begin to close itself up.

Honor Flights began as a response to the unsettling fact that every day our country loses hundreds of World War II veterans, members of the Greatest Generation who helped fight the Allies to victory and usher in an era of prosperity in the United States. But that’s just one of many unsettling facts about our veterans that need addressing.

Episodes like the one my uncle had 50 years after his war service may have been rare for him, but they aren’t rare for war veterans in general. Not now, not ever. Not even for the supposedly stoic Greatest Generation who we’re told simply “got on with it” after the war ended. In his book The Evil Hours: A Biography of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, war reporter and former Marine David Morris notes a 1951 study of 200 World War II vets that found 10 percent of them still suffered “combat neurosis.” Subsequent studies in the 1980s recorded continuing high PTSD rates among WWII veterans, especially among Pacific theater POWs, 85 percent of whom suffered from PTSD forty years after their service. But few Americans heard or took much notice of these findings. While many soldiers of WWII received a hero’s welcome on their return home, neither the government nor the public were interested in giving much attention to the veterans’ post-war psychological condition.

In Korea, American soldiers endured brutal weather conditions that left many of them with long-lasting health problems caused by extreme cold exposure. After the war they came home to much less fanfare than the World War II veterans had gotten, to national indifference by most accounts. (Dad came home to a port with some bunting and some family picture-taking by Lake Michigan.) The U.S. lost at least 36,000 soldiers in three years of warfare, but down the road the Korean War would become known as “the Forgotten War” by historians, and its warriors’ sacrifices and stories would get shuffled aside by the controversy over another brewing conflict in Asia.

The Vietnam War brought the first wide-scale awareness of PTSD and its prevalence among war veterans to the American public. But many veterans of that war still found themselves coming home from a military battlefield to an emotional one, as public opinions and disagreements about the war itself often took precedence over how to welcome home and honor its soldiers and foster their readjustment to their communities. There are arguments to this day over whether Vietnam veterans were treated with as much disrespect on their return home as national memory claims. (Were returning Vietnam veterans really spit on and called horrible names, or is that just a myth? What emotions and experiences prompted the Warriors Watch Riders, many of whom are of the Vietnam generation, to come up with the motto “Never again will an American warrior be scorned or ignored”?) But these arguments miss an important point, which is whether our nation was ever much effective in figuring out how to reintegrate veterans into American life after their war service, in acknowledging veterans’ ordeals and experiences and providing them with the resources and respect they need (and explicitly ask for) during their readjustment to civilian life.

Statistics from recent years show we’re still failing our veterans. According to the Dept. of Veterans Affairs, at least 22 veterans and at least 1 active duty soldier die by suicide per day. The VA also estimates the rate of PTSD among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan ranges from 10% to 20%. Meanwhile, every few years scandals involving VA and military medical centers recycle themselves, exposing the life-threatening delays, neglect, shoddy conditions, and malfeasance at some of our official veterans’ facilities. Our warriors continue to return from battlefields abroad hurt yet determined to heal, but the society that keeps sending these men and women to war continues to fail at addressing their hurt and helping them to heal.

It’s the veterans themselves who have consistently responded to these failures by organizing, by creating public rituals and building monuments that will force communities to remember and pay proper respects. And many local communities are trying to meet their veterans more than half-way in whatever ways they can. Honor Flights are one such attempt to make up for our long-standing national disregard and ignorance. The Veterans Network Committee of Northern Illinois is another such attempt, a local grass-roots group of vets and citizens with “skin in the game” that painstakingly plants a flag for every Illinois soldier sacrificed in Iraq and Afghanistan every year, that provides care and assistance in the form of holiday turkey dinners and overseas care packages and support groups to struggling veterans and distant active-duty soldiers, that crafts a three-day adventure to our nation’s capital for our aging warriors, complete with time for bonding and reflection, a bikers’ escort, a big-band serenade, and handmade quilts with over 100 hours of respect and gratitude sewn into them. Not that an Honor Flight for every American veteran is the answer to our country’s bureaucratic problems—in some ways an Honor Flight is just a gesture really. But it’s a gesture that involves a great deal of planning, and of listening and paying attention to veterans, as well as tremendous local and volunteer efforts. The big official veterans’ organizations might learn from these local efforts, from the grass-roots groups like the Veterans Network Committee of Northern Illinois. So might a few of our politicians—from all points of the political spectrum. Because if local communities and volunteer-run nonprofits can organize so well and give so much, what’s keeping the government from doing better?

Only a few weeks after my dad’s Honor Flight, we got word that one of the other vets on the trip had passed away. Rose of the Women’s Army Corps, the one who’d had her military record put on a big screen at the Women’s Memorial. Randy Granath would tell me when I spoke to him a couple weeks later that this is fairly common with Honor Flights. They almost always lose one or two veterans right after the trip. Sometimes it’s expected, sometimes not. Maybe some of them would’ve died even sooner if they hadn’t had the last few months of preparing for their trip to keep them going a little longer. My dad’s friend Harold, the first friend of his to go on an Honor Flight, died only a day after his return. At the very least, he and Rose and all the other vets who pass on go out with one more item crossed off their bucket list, and their families can say they know their veteran got the local respect and honor they deserved.

Dad, meanwhile, took time writing thank you notes to everyone he could—thanking all the people who thanked him for his service. He sent one to my mother, to my brothers and sisters, to his grandchildren, to me, to Randy and the VNC, even to the quilting ladies. He wanted the quilting club to know how much he appreciated their beautiful handiwork, and how he wished he could have had a quilt just like it in his army days, to protect him against the cold in the warzones of Korea.