From celluloid to "content"

Chicago's Essanay Studios, the AI threat, and the film industry strikes

“We have developed speed, but we have shut ourselves in. Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical. Our cleverness, hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost…”

When it comes to major film cities, Chicago isn’t a place that comes to the average moviegoer’s mind. Sure, it’s inspired some great flicks and TV shows: Some Like It Hot, The Blues Brothers, Thief, Hill Street Blues, ER. It was a perfect stand-in for Gotham in Batman Returns and the real backdrop for a lot of those NYC/Philly scenes in Empire.

But it’s nobody’s idea of an important film center. There’s no hub of filmmakers or studios here, despite the various film festivals the city hosts or the existence of renowned local film organizations like Facets or the film and video program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). It’s more of a theater town than anything, with Steppenwolf and The Second City our two biggest bragging rights.

But it wasn’t always this way. There was a time when Chicago was home to a pretty important film studio, a studio that introduced one of cinema’s all-time greatest characters. The studio building still stands too, even though it goes all the way back to the silent era. Which means Chicago was there almost at the beginning of the birth of film, when moviemaking innovation was a wild, wide-open territory and the medium was so very different than it is today, yet so familiar.

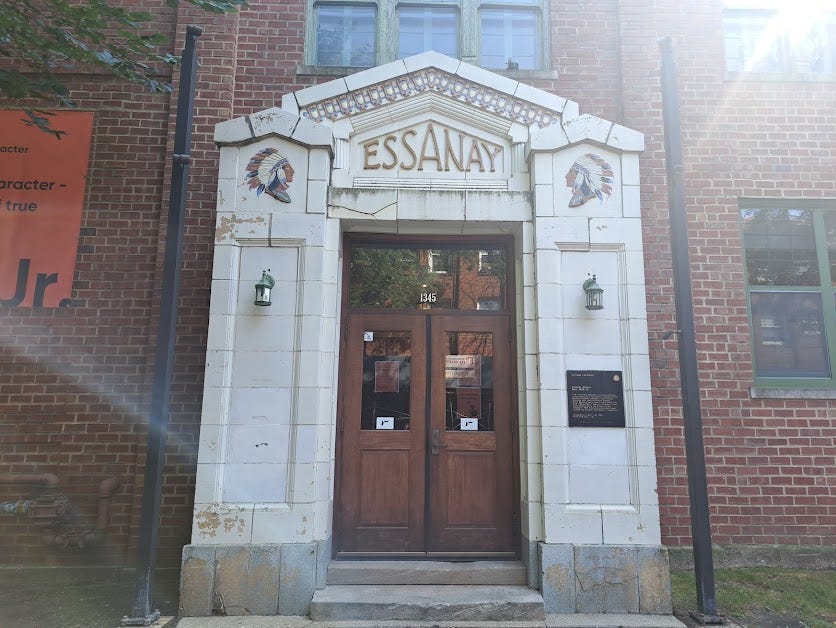

On the north side of Chicago is Essanay Studios, a former motion picture company founded in 1907. For nearly a decade, Essanay made films out of its Chicago studio until the city’s notoriously rotten winter weather forced many of its stars and filmmakers to pack up for southern California, where the motion picture industry had coalesced in a suburb of Los Angeles called Hollywood. But in that near-decade Essanay produced more than 1,000 films, many of them filmed on the Chicago lot that borders Andersonville and Uptown. Essanay’s star players included Gloria Swanson (a Chicago native), Wallace Beery, Francis X. Bushman, Lewis Stone, Ben Turpin, Colleen Moore…and Charlie Chaplin. It was Essanay that gave the world The Tramp, a 1915 silent film that introduced Chaplin’s beloved “Little Tramp” character as he came to be known around the world.

Essanay got its name from the initials of its two founders: George K. Spoor, who had been working in film in Chicago as early as 1897, and Gilbert M. Anderson, who had starred in the milestone 1903 film, The Great Train Robbery, a 10-minute silent Western in 1903 that is considered the first narrative film. Anderson was also one the first cowboy film stars, known as Broncho Billy Anderson. The two men originally called their new company the Peerless Film Manufacturing Company, but they soon changed it to Essanay after the “S” in Spoor and “A” in Anderson.

Essanay’s first studio was at 510 Wells Street in Old Town, which was where its first film was shot, An Awful Skate: or The Hobo on Rollers, filmed and released in July 1907. It starred Ben Turpin, the studio’s janitor, who would become known for his trademark cross-eyed comic characters. The film was advertised as a “tremendous laugh-making picture that will make a warm weather audience wilt.” It cost a couple hundred dollars to make but earned thousands upon release. (And they say Jaws was the first summer blockbuster!)

A year later, a bigger studio lot was built at 1333-45 W. Argyle. This is the location that stands today.

According to a (very charming) 1909 article in Moving Picture World, the studio at Argyle had a “daylight studio” immediately south of the indoor studio where outdoor shots could be filmed. The article’s author marvels at the construction of a padded cell (“not the usual painted upholstery, but the real thing”) for a new production called The Curse of Cocaine. (You can always count on Chicago for bringing the gritty melodrama.)

I love the article’s harrowing yet glamour-tinged account of the studio’s film processing department: “In the dimly-lighted developing rooms a dozen or more white gowned young ladies were busy putting the thousands of feet of celluloid strips through the various baths, or chemical processes, necessary in the developing of the films.”

In 1909, Essanay built a lot in Colorado to film more of its Westerns. Then in 1912, they opened a lot in Niles, California, where the canyon setting and the year-round warm weather provided a better site for shooting Anderson’s Broncho Billy films. In 1914, Essanay successfully wooed Chaplin away from Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios. Apart from landing Chaplin, Essanay’s other contributions to motion picture history include the first film version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1908), the first biopic (of many to come) of the outlaws Jesse and Frank James (The James Boys of Missouri, made in 1908), and the first slapstick pie-in-the face scene (1909’s Mr. Flip, with Turpin on the receiving end).

Chaplin spent two years with Essanay before Chicago’s cold weather and Chaplin’s own demands for a bigger salary and more creative control sent him back to southern California. By this time, Essanay was struggling. The company tried forming partnerships with other film studios to keep going. But the writing was on the wall that the future of motion pictures in America was in sunny Hollywood, not the north side of Chicago.

Norman Wilding, a producer of industrial films, took over the studio on Argyle for several decades. Then WTTW, Chicago’s local public television station, took it over for a short while before selling it. The Midwest office of Technicolor had a lease in the former studio for another while, as did Essanay Stage and Lighting Company. Today, St. Augustine College owns part of the building. The site was designated a Chicago landmark in 1996.

As for the “S” and “A” of Essanay, Spoor died in 1953 in Chicago at the age of 81. He was a true innovator in film, having invented one of the first film projectors for larger screens as well as an early attempt at 3-D film. Anderson died in 1971 in Hollywood at age 88. (Some reports say he was 90.) He left the movie industry in the 1920s and lived in obscurity until 1958, when he received an honorary Oscar for his pioneering film career. Spoor had received his own honorary Oscar 10 years earlier, and Chaplin got one in 1972. All were well deserved. Anderson, however, is the only one with a Chicago park named after him: Broncho Billy Park, located at 4437 N. Magnolia in Uptown, not far from the Essanay building.

So there’s Chicago’s first great claim to film fame. If I had to pick our second greatest movie contribution, I’d go with the fact that our city was once home to not one but two of the country’s most famous and respected film critics: Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert.

Both men left an indelible mark on the city and the journalistic craft of film criticism. Siskel, who wrote for the Chicago Tribune, has a beautiful theater named after him, the Gene Siskel Film Center on State Street, which partners with the film program at SAIC. Right across the street, Ebert has a marker in the sidewalk under the marquee of the Chicago Theatre. Ebert also has a statue and a film studies center named after him in his hometown of Champaign/Urbana in central Illinois, plus a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the first film critic to get one. He was also the first film critic to receive a Pulitzer Prize, for his work at the Chicago Sun-Times.

I was inspired to write about Essanay and Chicago’s important film contributions by the ongoing strikes in the American film industry. As I write this, the Writers Guild of America (WGA), which represents writers in film, television, and radio, and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA), which represents film and television performers, have both been on strike for several months regarding wages and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in film and television.

Each week since the strikes began, some celebrity or other has made the news for some comment or action they’ve made regarding the strikes. This past week it’s been Drew Barrymore, who unwisely planned to return to production of her talk show without writers, until both WGA and SAG members called her out for scabbing. (In fairness, others who’ve announced plans to cross the writers’ picket line this past week include Bill Maher and Chicago gal Jennifer Hudson. Say it ain’t so, Jen!)

As a nobody, I can’t pretend to really know what’s at stake in the film industry. But that doesn’t mean I can’t see writers’ and actors’ point about AI. I’d say most of us these days have some concerns about AI and its impact on people’s work and livelihoods, regardless of what your own work is. As a freelancer, I’ve already had language added to my contracts forbidding the use of ChatGPT or AI for writing content, and I was only too happy to see these clauses added. To me, it means my employers are looking out for my labor and the skills I’ve acquired over the course of my career as a working human being.

On the flip side, I’ve also had one recruiter contact me so far for work that involved writing content that would be used to program and improve the performance of AI content-creation software. In other words, to do work that would put me and other writers out of work in the long run. Needless to say, I ignored the offer. But it sure scared me.

For a while now, I’ve been dismayed at the way the word content gets thrown around these days to describe everything from truly creative work to news articles to Insta posts to advertising copy. (Believe me when I say I’ve heard the term used in the laziest ways.) Why can’t we just call a thing what it is? An article. An editorial. A movie. An advertising jingle. A company newsletter. A sitcom script. An Instagram post. A photo. A film review. When did it all become this bland behemoth known as content?

It’s just a word, I know. But then again, that’s what those who defend the use of AI to produce written materials might say about any and all kinds of writing. It’s just words, just language. Anyone can do it. And now, AI can do it all for us—from the writing to the spell-checking to the editing to the mysterious, sometimes glorious, sometimes wretched creative bumbling and brainstorming that has always been strictly the domain of us humans. Only humans create art. Only humans have the nuanced, messy experiences that can lead to the creation of a poem, a screenplay, a joke, a novel, or a cheerful email to a troubled friend. That’s what film and TV writers do, and that’s what the people who play out the words of film and TV writers do as well. That’s what movies are for. To serve and represent our humanity.

Ask yourself, can AI really produce the kind of intimate, thoughtful, well-written film criticism that won Roger Ebert a Pulitzer? Can it produce the kind of barbed yet mutually respectful arguments that made Siskel and Ebert so fun to watch on Sneak Previews and At the Movies? Can it inspire the same kind of free-wheeling, throw-it-against-the-wall-and-see-if-it-sticks innovation that typified the early film industry? Is there even a chance that AI can capture the genius that drove Charlie Chaplin?

As for Chicago, it may not be a movie city, but it is a labor city. Considering Chicago’s history as an epicenter in the struggle for workers’ rights, sometimes I wonder what the film industry would look like today if Essanay never left and movie stars and filmmakers had all flocked here instead of Hollywood. Would the unions be even stronger? Would there have been less glamour but more realism in the movies throughout the early and classic years? Would there be more of an alliance between technical workers and creative workers?

We’ll never know, of course. But when I think about the different roads the early American film industry could have gone down, I think about how artists, and all people, have a tendency to weather change overall. Films still do get made in Chicago, and the city still produces great talent. And out in Hollywood, the industry has survived numerous creative (and literal) earthquakes. Sound films were thought to be a major threat at first. People thought it would be the end of movies. It ended quite a few careers, sadly, but movies went on, and Hollywood even came to laugh about it all in one of the greatest films of all time, Singin’ in the Rain, which told the story of the shift from silents to talkies. I’m not sure if AI is more of a real threat than “talkies” turned out to be—maybe out current worries are just classic tech anxiety. Or maybe there’s a real battle for our humanity ahead. (I know, that sounds like the plot of a cheesy Hollywood movie. But everyone loves a cheesy movie from time to time.)

Other earthquakes in film history include the end of the studio system, the threat of McCarthyism, and the fight for artists to have individual control over their careers and creative work. Charlie Chaplin was one who was at the center of all of those earthquakes. His desire for more control was one reason he left Essanay. And the human spirit was a foundation of all his films.

Film critics and historians say before Essanay, Chaplin’s comedy in the Keystone films was meaner and more farcical. Crude and cruel. Pure slapstick. Yes, the little guy with the bowler hat first shows up in one of Chaplin’s Keystone shorts in 1914. But it was at Essanay where he introduced more sophisticated storylines and finely observed physical comedy, and where he developed “The Tramp” into a more textured human character.

After Essanay, Chaplin went on to the feature-length films we all remember him for: The Kid, The Gold Rush, City Lights. His storylines became more emotional, yet he still delivered the bumbling physical humor and the big laughs. In Modern Times he told a story about people getting caught up (literally!) in technology and machines and the way progress and industry can dehumanize us all.

Then in The Great Dictator, Chaplin caved to technology himself and gave us the first film in which we got to hear his voice. He used it make a famous plea for humanity in a speech at the film’s end. That quote at the top of this post is from the speech. When Chaplin was given his honorary Oscar, some of those same words from the speech were used to introduce him, and Chaplin came out to a standing ovation that lasted a history-making (for the Oscars) 12 minutes long.

On the one hand, if artists survived the so-called technological and political threats to moviemaking back in the day, maybe there’s no doubt they’ll survive them now. Technology, after all, is what allows us to enjoy films, radio, TV, streaming, the whole lot of it, to begin with. And politics…politics is gonna do what politics is gonna do. In the end, I think art always ends up having the last word, even under the most fascist regimes. (Ozymandias, anyone?)

But Chaplin’s work—both his physical comedy and his words—show us that to fear the machine is an ever-present human concern, and maybe the best way to combat it is to assert your control, your identity, your humanity through art and the act of creation. We’ve all been given gifts of some sort. Chaplin had the gift of humor and comedy. Writers have the gift of words. Actors have the gift of empathy and role-playing to make audiences believe they’re seeing the real thing happening before their eyes. These are all skills and tools some of use to make a living and/or make art. That’s really what the current writers’ and actors’ strikes are about. They want their say in how their work is used and they want to use the skills and tools they have. Technology is a human tool. We get to use it and replace it as needed, it shouldn’t get to use or replace us.

Connections: There’s a lot of stuff out there (dare I say content?) about the strikes. The only couple things I’m going to link to here is, first, this recent Deadline interview I enjoyed with director Richard Linklater, in which he talks about this era of content creation we’re living in versus the indie film heyday of the 90s, when Linklater came up (Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise). A solid quote:

“Tech companies came in, and we went from film being art, with value, to it becoming content that you click on.”

In the interview, Linklater mentions a new documentary, The YouTube Effect by Alex Winter. (Hiya Gen X! Winter is lodged forever in your hearts and memories as Bill from the Bill and Ted movies. Bill was the not-Keanu-but-equally-cute one.) The doc has a lot to say about content creation and its effect on the news and film industries—and on our brains. You can find it on streaming channels, but here’s the trailer. Some of Winter’s other films include a doc about Frank Zappa, the kind of original, way-out-there artist whose work AI never could duplicate.

Finally, here’s our buddy: