In the past few months, I’ve seen Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis three times. The first was out of curiosity. I’ve always been a fan of the real Elvis, but Luhrmann’s movie kicked my fandom into overdrive. After the first viewing I fell down an Elvis rabbit hole, and in many ways I’m still not ready to come up for air.

I think some of the renewed fandom was connected to my dad. On February 8, 2023, my wonderful, courageous, beloved father passed away at age 94. He’d been declining since August 2022, and a week before he died he was placed into hospice care at home. It’s been an emotional time, to say the least, and I think part of me has connected the emotions of love, loss, heartbreak, and admiration to the music and life of Elvis Presley.

Part of it was distraction too. I knew what was happening to my dad, what the inevitable was. But part of me couldn’t process it. It was scary and unsettling. So I processed some of it through Elvis, whose story and demise are well-known, and therefore familiar and safe, to all fans and all Americans.

Elvis and my dad had almost nothing in common. One grew up in the Deep South, the other in Chicago. One was world-famous, a rebellious trendsetter turned over-the-top American tragedy, an unapologetic mama’s boy, an icon, a seemingly effortlessly charismatic showman. The other a dedicated family man who worked for over 30 years at a phone and telecommunications company and had a 68-year love affair with his wife (my mother). One succumbed to addiction and congenital health problems when he was only 42. The other played tennis into his 80s, living into his 9th decade.

Both grew up in disadvantaged circumstances (to understate it) though. Both knew hunger as children. Both served their country. Both worked hard to support large families (my dad six kids, a wife, and the occasional extended family member; Elvis his immediate and extended family of aunts, uncles, cousins, longtime loyal Memphis friends, band members and staff, and hangers-on).

While my dad was dying, I spent a lot of my spare time listening to Elvis’ music, watching other movies and documentaries about him, reading biographies and essays about his life and influence. More than one of the classic essays about Elvis quote from a William Carlos Williams poem, “To Elsie”: “The pure products of America / go crazy” is the opener. A great one, to be sure, but after reading the whole poem, I didn’t think it suited someone like Elvis, someone who grew up poor and southern in the pre-Big Media age. Someone “authentic.” Someone “problematic.” Someone real.

“To Elsie” is a great work by a great poet, but it’s in the voice of an upper middle-class voice (or “high class” as the song “Hound Dog” puts it) speaking about “low-class” working people. It lacks the straight-on emotional wallop of an Elvis song. Like “Heartbreak Hotel” or “In the Ghetto.” Like the gut-wrenching version of “Unchained Melody” that Elvis performed in the last weeks of his life and that brilliantly closes out the Elvis movie.

Elvis always sang from the heart and gave listeners and audiences the emotional experience they were seeking. “To Elsie” works on many levels, but not that kind.

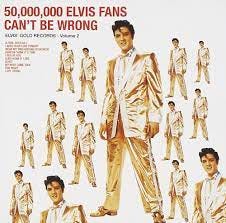

In Peter Guralnick’s essential 2-volume biography of Elvis, which was published in the 1990s and which I’d been long meaning to read, I came across the factoid that Elvis first wore that famous gold suit in his first concert in Chicago. You probably know the suit. The one featured on the album cover of 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong: Elvis’ Gold Records, Volume 2 in about as many manifestations.

The suit was designed by the legendary Nudie Cohn, who used gold leaf lamé for the suit that included jacket, pants, belt, necktie, and even gold shoes. Elvis’ manager, Colonel Tom Parker, claimed the suit was worth $10,000, but the real price was $2,500 and a goldmine in publicity and cultural impact.

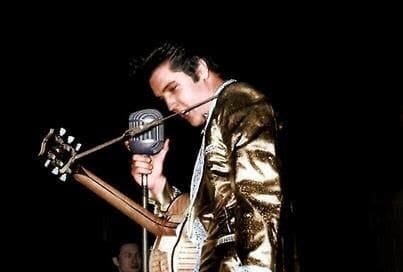

After the photo shoot for the album cover, Elvis’ first appearance in the suit was on March 28, 1957 to a crowd of 12,000 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, which kicked off his ‘57 tour. He would wear the full suit for only two more performances, claiming it was too hot and constricting to perform in. Or maybe he just didn’t like the look. Maybe he didn’t like being treated and gussied up like a commodity, like a walking, singing, dancing gold mine for his manager and recording company, rather than a genuine artist.

According to Guralnick, during the Chicago show Elvis dropped to his knees at one point and left $50 worth of gold spangles on the stage. The Chicago Tribune covered the show and reported that 13 girls fainted and had to be carried out, another girl clung to the stage and required 2 men to pry her away, and yet another teenage hellion swung at a cop with her purse and hit an 18-year-old usher instead.

Before the show, Elvis held a press conference at the Saddle & Sirloin Club at The Stock Yard Inn, a former hangout of Chicago meatpacking execs at the former Union Stockyards. Elvis good-naturedly posed with a hound dog and wore a considerably less flashy red and black vertical-striped jacket, though he did show off the gold shoes.

These days, like Elvis, the International Amphitheatre, Saddle & Sirloin, and stockyards are long gone. But the gold suit survives, at Graceland.

Thinking about Elvis in Chicago and his gold suit made me think of a poem by another giant of American poetry: “Nothing Gold Can Stay” by Robert Frost.

Nature’s first green is gold, Her hardest hue to hold. Her early leaf's a flower; But only so an hour. Then leaf subsides to leaf. So Eden sank to grief, So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.

To me, this is the poem we should be quoting when it comes to Elvis. It seems to just speak to his myth. The tremendous beauty of his youth and explosive energy with which he burst onto our national consciousness, the trading of it all in for the army and then Hollywood, the fabulous bling and recklessness of his dirt-poor-sharecropper’s-son-turned-millionaire lifestyle, the shortness of his life, the generational impact of his music, and the question of his continuing relevance.

Does Elvis still matter? Maybe it’s too much to ask of anyone for too long after they pass. Nothing gold can stay. The gold outfit may be hanging in a museum, inside the mansion paid for with so many gold records. But the human being who inhabited it all was as fragile as a summer’s leaf in the final days of fall.

Maybe I’m overthinking it. But Frost’s poem doesn’t, and neither did Elvis’ music—at least, if they did, they didn’t let it show. Both men made their art look almost simple and easy. Sincere. Original. American.

It turns out I’m not the only to make this connection. In The Outsiders, S.E. Hinton has Ponyboy, one of her rebellious, misunderstood “greaser” boy characters, recite Frost’s poem. In the novel’s heartbreaking end, another greaser, Johnny, tells Ponyboy to “Stay gold.” The greasers are wilder, poorer, stuck on the losing end of life in their Oklahoma town, especially compared to the rich kid “Socs” who they end up rumbling with. Hinton’s story (also seemingly simple, like Frost’s poem and Elvis’ music) draws distinct lines between the greasers and Socs in everything from dress to musical tastes. The greasers love Elvis, while the Socs have moved on to the Beatles. It is 1965 after all. The Socs think Elvis “is out,” but the greasers think he’s “tuff.”

In Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 movie version of The Outsiders, the greaser kids all clearly take their look from Elvis—well, from poverty too. Coppola supposedly wanted a wall-to-wall Elvis soundtrack for the film. Not until a director’s cut released in 2005 did he get his soundtrack of Elvis songs. (Stevie Wonder provided an original song for the 1983 film called “Stay Gold.” Not one of my favorites, but Wonder is another one of those legends whose lesser work still beats most musicians’ best.)

As for Chicago, 1957 wasn’t the only year Elvis graced the city with his presence. In the ‘70s he performed at least 3 more times in Chicago: in June 1972, October 1976, and May 1977. By this time, he was in his era of jumpsuits, patterned silk shirts, wide heavyweight champ-style belts, and white bell bottoms. His very last time in Chicago, on May 2, 1977, he wore his Mexican Sundial jumpsuit, a white suit with the Aztec calendar on the front and back designed by Gene Doucette.

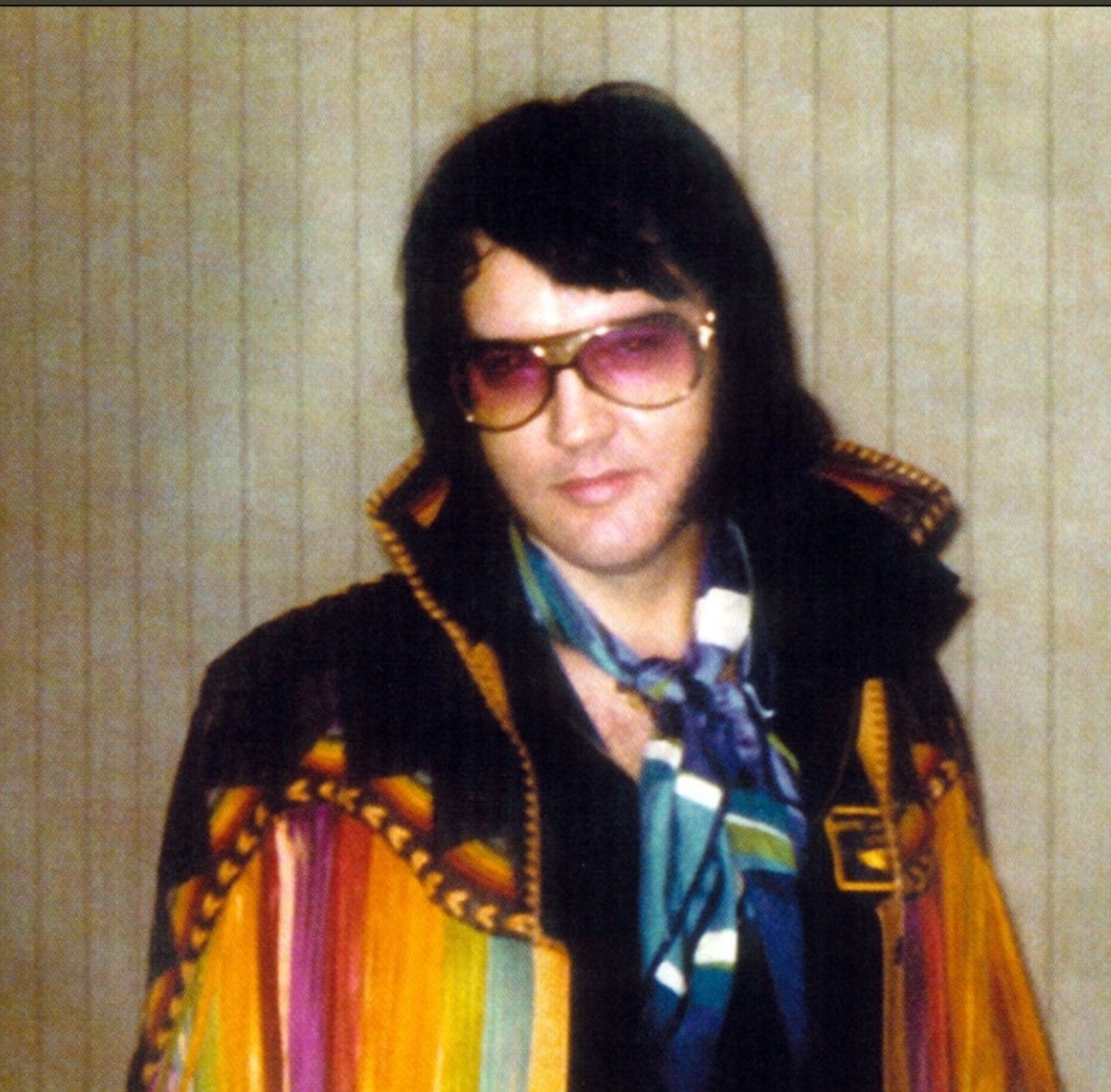

But my favorite piece of Chicago performance Elvis apparel is this beauty below, in a pic taken by a fan (Elvis always made time for one) at the Arlington Hilton.

The rainbow fringe leather jacket Elvis wears here was made by North Beach Leathers, who made several leather pieces for him. This isn’t even a great quality photo, but check out that detailing! The shades are also a custom design, by Dennis Roberts of Optique Boutique: aviator-style with gold frames, Elvis’ initials on the bridge, and the letters TCB (for “takin’ care of business”) with a lightning bolt (symbolizing “in a flash” … so TCB in a flash) engraved on the sides. I love the look because only Elvis could pull off this combo of rainbows, silk scarves, aviators, wacky acronyms, and personal branding. Also, the little smile. This was taken in October 1976. Less than a year later, he was gone.

No discussion about Elvis and Chicago would be complete without mentioning “In the Ghetto,” the Top 10 hit written by Mac Davis (who also wrote “A Little Less Conversation”) that tells the story of cyclical poverty and violence. The ghetto sung about is in Chicago, even though Davis claimed he was inspired to write the song by the experience a black friend of his growing up in Lubbock, Texas. Who knows why he chose Chicago of all places, instead of a Southern city. My take is Chicago’s harsh and crappy winter weather (“As the snow flies / on a cold and gray Chicago morn”) lent itself perfectly to the hard times the song describes. And in the ‘60s, Chicago was in the news as a place of racial unrest and turmoil, not least of which was violent riots led by white residents against Martin Luther King in ‘66.

Maybe Davis had no business setting the song in a Northern city, and maybe Elvis had no business singing it. By the time he recorded it, in 1969, he was a filthy rich icon, a once-poor Southern white boy singing black people’s music with poverty well behind him. Except anyone who’s experienced real poverty will tell you that you never really leave it behind.

To the end of his life, Elvis was haunted by the poverty of his childhood, as well as the death of his twin brother at birth. His beloved mother’s death in her 40s when Elvis was at the peak of his early career was another nightmare to cloud his dreams until the end. In Guralnick’s rigorous biography of Elvis, you can tell how much the memory of poverty preoccupied him by frequent “jokes” in interviews and private conversations like “Last thing I remember, I was driving a truck.” He and his father never stopped fearing it would all disappear “in a flash” and they’d find themselves back in Tupelo, Mississippi.

In that context, his excessive spending and lifestyle make more sense. You desperately want all the stuff you never had as a kid to prove to yourself how far you’ve come—and to erase the memory of those hard times. Hundreds of Cadillacs. Flashy jewelry. Flashy clothes. An antebellum-style mansion, the kind that was never meant for “poor white trash” like you much anyone of color. And as long as you can keep acquiring it all, you can keep telling yourself that poverty’s over and done with you.

Except it isn’t. Not in your mind or sense of self. Since my dad died, my mom’s been talking to me about this—how my dad’s childhood affected his work ethic and sense of family. He never wanted to end up back like what he experienced as a child, and he never wanted any of us to know that kind of precariousness. My dad’s method was the more sensible way, certainly compared to the excess of Elvis. But Elvis’ way also involved singing his way through his troubles and fears.

So despite his apparent distance from the setting and struggles of “In the Ghetto,” he sang it like he felt close to it. Because he was—through the hunger of his childhood, to his twin’s stillbirth just half an hour before Elvis’ birth, to his mother’s own death depriving him of her loving guidance the rest of his life and career.

The press made a field day out of it all, out of his roots and family struggles. Hillbilly jokes, disturbingly sexualized nicknames like “Elvis the Pelvis,” lurid tabloid tales including a published photo of him in his casket taken by a cousin desperate for the cash. Since his death, the reek of classism remains in the neverending lazy jokes, imitations, and caricatures.

Nothing gold can stay. That’s comfort when confronted with the worst and sorrowful when enjoying the best. I’m glad we still have Elvis’ music to remember him by, and Luhrmann’s movie seems to have revitalized interest in his work and conversations about his relevance and impact. Those conversations should include class and classism as much as they do race, gender, and sexuality.

Listening to Elvis songs didn’t make it easier for me while my dad was dying, but it did help lessen the silence and isolation you feel when you lose a parent. We all process things in our own ways. Maybe there was also a little of what Truman Capote once said about his tortured protagonist in In Cold Blood. It’s as if they were born in the same house, and Elvis took one door out, and my dad took the other. And as Robert Frost said in another great poem, that made all the difference.

Thanks for reading. In May, I’ll share more about my dad.

On the topic of “In the Ghetto,” this brilliant longform article about the song by John Ross puts it in the context of its time and has some insightful stuff about Elvis’ connection to the song and his vocals and phrasing.

When I say I fell down an Elvis rabbit hole, I mean I really cannonballed down one, which isn’t hard to do given all the exhaustive blogs and books out there by other raging superfans. For more about his gold suit, check out the Elvis History Blog. A good site for articles and interviews (with everyone who ever met Elvis it seems) is Elvis Australia.

Want to know all the details about every concert he ever performed in Chicago or elsewhere, including what suit and belt he wore, how his band dressed, how many attended, and what the ticket stub even looked like? Well, the Elvis Presley In Concert site has a database that will allow you to learn it all.

And whatever happened to Chicago’s International Amphitheatre or the old Saddle & Sirloin Club? A site dedicated to Scotty Moore, Elvis’ original backing guitarist, will fill you in! I know…of all places.

Peter Guralnick’s Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love make up the best regarded Elvis biography. For those seeking a considerably shorter tome, check out Bobbie Ann Mason’s Penguin bio. As a fellow Southerner who grew up in the time of Elvis’ success, Mason offers a sympathetic view that doesn’t condescend or patronize him or his roots. As an acclaimed novelist and short story writer, Mason also knows how to tell a compelling story, rather than compiling a bunch of dusty facts or half-baked anecdotes.

Finally…the movies. I like Elvis, obviously, even if I thought it as heavy-handed at times and left a lot out. But I guess even Baz can’t fit in all the epicness that made up Elvis’ life. I think it was robbed of at least 1 or 2 Oscars. I mean, none for the costumes even? The one that broke my heart though was cinematographer Mandy Walker’s loss to All Quiet on the Western Front. Had she won, she would’ve been the first woman to win for cinematography. She’s only the 3rd woman ever nominated in the category.

Meanwhile, I haven’t seen every movie about Elvis out there, but my favorite of those I have is Elvis & Nixon for Michael Shannon’s great portrayal of the King. Austin Butler did a great job, but I have to credit the Chicago-trained Shannon for capturing the humor and humanity of Elvis. Skip to 53:48 below for a great monologue in the moments before Elvis is taken into the Oval Office to meet Nixon (Kevin Spacey), when Elvis tells the story of his twin brother Jesse.