Since the pandemic, I’ve been thinking a lot about age. About the ways ageism is dividing generations during an already divisive time. And what it’s like to be a woman on the far side of 40 (or 50, or 60, and so on) in our culture.

One reason is the ageism of COVID-19. In the United States, more than 90% of COVID deaths have been in people over age 50. Raise the age to people 65 and over and the death rates are greater for each older age group than all the younger age groups combined.

In many ways, this is impersonal ageism. It’s nothing against older people—just a fact of nature that our immune systems weaken as we age and viruses strike vulnerable systems. But COVID has exposed a more insidious kind of ageism. The kind that’s emboldened commentators to shrug off safety protocols, saying those who’ve died “were on their last legs anyway.” Or that’s fed into intergenerational blame games on social media and offensive takes that wiser editors would never allow to see the light of day.

Ageism also marred the vaccine roll-out earlier this year. Most states used extremely glitchy, appallingly ableist online appointment systems that many older people, who tend to fall on the negative side of the “digital divide,” couldn’t navigate or even access to schedule their life-saving vaccines.

Aging is not for the faint of heart

But I also have personal reasons for thinking so much about age these days. As a caregiver (along with my siblings) of elderly parents of the invisible Silent Generation, I’m sensitive to how old people are treated and talked about in our culture. The older you or the people you love get, the more you become aware of what a stigma aging is in a youth-obsessed society.

Not only are old people themselves pushed to the margins in our culture, so is any discussion of aging beyond ageist jokes and stereotyping. The real experiences of older adults (and the people who look after them, who tend to be middle-aged women or other elderly) go unheard.

Over the course of the pandemic, I’ve heard many takes on what it’s like to be a parent of young children during this stressful time but comparatively little on what it’s like to be a caregiving child of elderly parents. Even more rare are accounts from the elderly themselves. For every thousand think pieces about millennials and boomers, there are few about the extremely at-risk Silent Generation and their caregivers. It’s the exact opposite of what a healthy society should be doing right now. Studies show everyone benefits the more different generations communicate and interact with each other. The more you get to know older people while you’re young, the more you understand the natural trajectory of life and the wisdom and resilience of experience.

Another personal reason is my own aging. I went through menopause during the pandemic (an experience I wrote about, with a food and poetry twist, for the University Of Tucson Poetry Center’s Poetry Potluck series). It was a lonely thing going through a major life and health change without being able to spend time with other women my age, to even see them due to social distancing and quarantine. Many women report feeling suddenly “invisible” in society after reaching 40 or 50—but of course, with social distancing, the invisibility became literal.

In the workforce, ageism affects men as well but begins earlier for women and occurs more often, compounding the sexism many women experience and limiting their careers and earning power even more.

The Older Woman Artist

Since this is a newsletter partially about outsider art, I want to delve into how aging is represented (or not) in the work of older women outsider artists.

A (weak) justification for ageism is that people lose relevance as they get older. They fall out of touch with their own culture. They don’t, or can’t, keep up with trends. Their art doesn’t have the power of younger artists.

This, of course, is a giant manure pile of rationale for marginalizing the middle-aged and elderly, as well as for our younger selves’ tendency to remain deeply in denial about the inevitability of death and our physical vulnerability.

Most ageism is really anxiety about death and illness, and there’s no one better to confront this anxiety in our culture than an older artist. Yet the art world and art competitions most often reward younger artists, overlooking those who started late (especially common among women artists) or lacked the crucial support and mentoring they needed to break through at a younger age (also typical of women artists).

Recent discussions on older women artists declare a breakthrough of sorts in ageism and the art world, based on the late-life success of women like Cuban minimalist Carmen Herrera and Japanese infinity room inventor Yayoi Kusama. Herrera finally sold her first piece at 89, despite painting since the 1930s and deep, longtime ties to the elite art world. Kusama first found success in the 1960s, only to see her ideas frequently stolen by male artists, before succumbing herself to mental illness and institutionalization and falling into obscurity.

Their success is encouraging, but shouldn’t be divorced from necessary conversations about ageism and sexism. Some critics consider the new appreciation for older women artists in part due to the prohibitively high prices for work by male and younger artists. “High quality at bargain prices.” In other words, women’s work is still being undersold. Another factor is the desire by galleries and dealers to attain “woke” brownie points for “inclusivity.” In other words, older women are still being patronized, still treated like outsiders.

What does the work and legacy of two of Chicago’s most famous female outsider artists tell us about the realities of being an older women artist?

Vivian Maier: The Nanny Photographer

Vivian Maier moved to Chicago in the late 1950s and shot thousands upon thousands of photos capturing the city’s faces and places, turning the unregarded and ordinary into the extraordinary. Recognition came too late, but her posthumous fame spread like wildfire.

Like outsider artist and fellow Chicagoan Henry Darger, Maier was secretive about her art and seemed to have had no formal training. She never married or had children, and died in poverty and obscurity, literally just as her remarkable art was being salvaged and discovered.

She was born in New York in 1926 and grew up between the East Coast and France. In the early 50s she settled in America for good, working as a nanny and later as a caregiver to elderly. By the late 50s, she’d moved to Chicago, working in a series of homes in the wealthy North Shore suburbs. (For a short while, she even nannied TV host Phil Donahue’s kids.) Socially, she was a loner, but a woman with sharp intellectual interests who loved movies, followed politics, and traveled around the world.

Maier began taking photos at a young age, starting with a simple Brownie box camera before switching to a Rolleiflex and single-lens reflex cameras. She photographed the children she took care of as well as the people and objects she encountered on walks in the city and around her employers’ suburban neighborhoods. She took photos on her many travels and even of celebrities passing through town on publicity junkets. She also took photos of herself—sometimes direct shots in mirrors, often fractured or blurred self-portraits as seen in shadows or distant reflections in a store window.

She never sold, published, or exhibited a single one. She didn’t even develop all of them, accumulating hundreds of rolls of undeveloped film by the end of her life.

Beginning in the 1970s, Maier’s employment record became spotty. The children she used to look after grew up, and Maier, in her late 40s and 50s, found it harder to find long-term employment. By the 1980s, she entered a period of financial instability that would trouble her until her death. She had bouts of homelessness and kept her photos and other belongings in storage lockers. In 2007, these items were auctioned off to several buyers.

In 2008, Maier fell on a patch of ice and was hospitalized. She lingered until April 2009, when she died at age 83. She had no idea, as she lay dying in the last year of her life, her work was being snapped up for nearly $100 a shot. One of the buyers of her auctioned storage items had begun selling her photos on eBay and uploading them to Flickr, with viral results. Having bought them through an auction house, he had no idea who the photographer was until he finally found a photo lab receipt with a name on it. He Googled the name. And there was her death notice. He’d missed her by only a few days.

It’s easy to understand why so many people fell in love with Maier’s work. There’s the nostalgia of New York and Chicago as viewed in black and white—and her striking choice of subjects. Maier noticed the kind of people who usually don’t get noticed.

Many of her photos were of people rendered invisible or unimportant in American society—laborers in the middle of a job task, homeless people sleeping in parks or doorways, black Chicagoans hawking goods at the city’s famous (and long-gone) Maxwell Street market, children lost in a world of their own on the beach or on the street. Maier paid especial attention to older people, particularly middle-aged and elderly women.

Are people drawn to Maier’s photos because they too feel invisible and thus seen by her art? Or do they feel drawn to Maier herself, a woman who went unnoticed in life?

In truth, Maier deliberately kept her talent a secret, for reasons we’ll never know. Maybe she felt anonymity freed her to take photos and pursue her art without much fuss or objection. People may be more likely to ignore a harmless-looking older woman taking their photo than they would a flashy pro or pushy reporter with expensive equipment. In that regard, being an older woman can have its advantages—the freedom of the outsider.

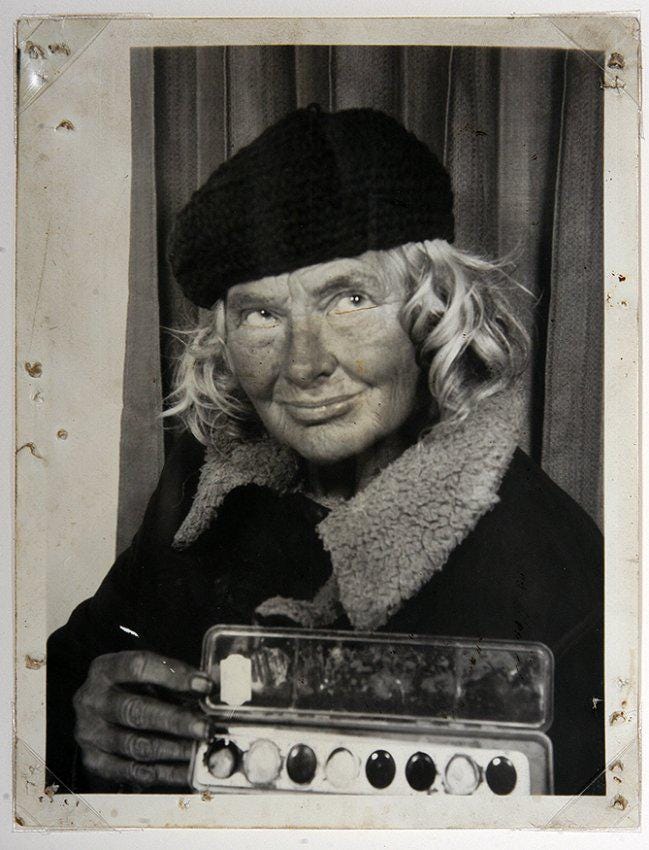

Since May, the Chicago History Museum has been hosting an exhibit of Maier’s color photographs, many of them never seen before by the public. The exhibit includes a photo of the artist dated in the 1950s, when Maier would’ve been about 30. It’s a good, clear shot, so it’s easy to see why the curator chose to exhibit it. But I wish one or two clearly showing an older Maier had been included, like the photo at the top of this newsletter. One that shows the age in her face, the experience of her life. The later one more truthfully shows the face behind the photos in the era largely represented in the exhibit (the 1970s). It also gives a greater sense of the passing of time and the accrual of experience in her work, the sense of change as well as continuity in a woman’s work practiced over decades—reminding audiences they are viewing the art not of an eternally youthful Mary Poppins-like character, and forcing them to reckon with their preconceptions of aging women and the supposed decline of older adults’ ability and relevance.

Lee Godie: The Bag Lady Artist

By contrast, Lee Godie’s photography gives audiences no chance to ignore the fact of her age. While her paintings depict youthful women and men (or “princes”), her photos all depict herself in her 60s through her 80s.

Godie’s background is as mysterious as Maier’s, maybe more so. She was born sometime between 1900 and 1910. (“I don’t celebrate my birthday,” she once said. “I celebrate my status as an artist.”) In Chicago, or in some place called Mudtown, Illinois—which may actually be Chicago. She married twice and had three or four children. Two died at a very young age. She had moved to Washington state by the 1940s, then disappeared after the end of her second marriage to re-emerge 20 years later on the streets of Chicago.

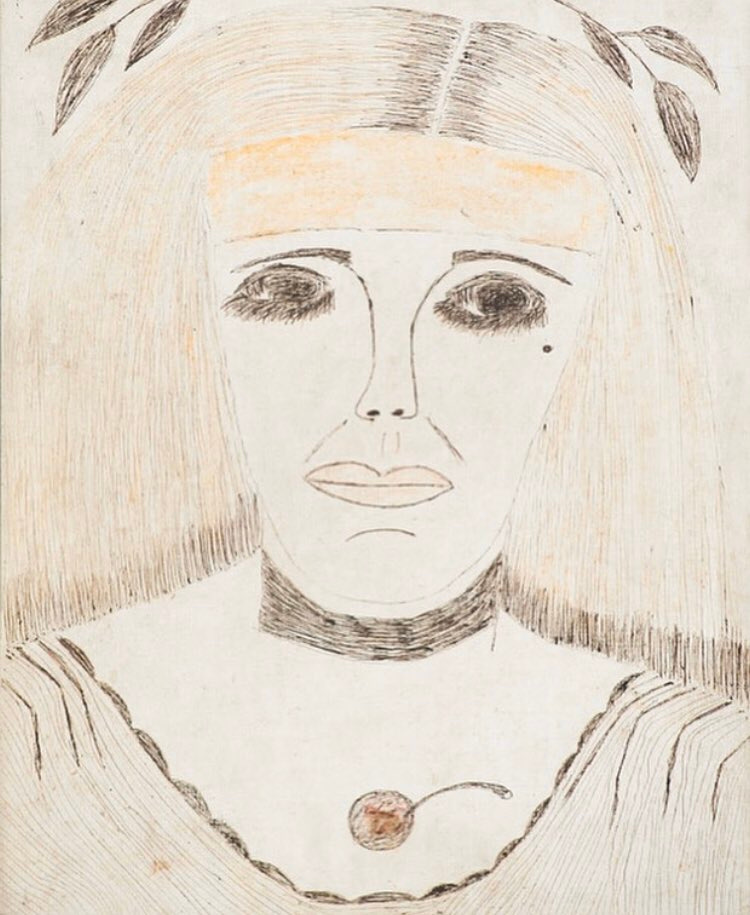

In Chicago, Godie became a local legend, often seen on the steps of the Art Institute, hawking her paintings and assuring would-be buyers that she was as good as Cezanne. She drew portraits of women and men with oversized eyes and long lashes, looking straight ahead or off to the side, often in profile, wearing large hats or old-fashioned attire. Sometimes she included natural elements like leaves or flowers and Chicago landmarks like the Hancock Building, with slogans scrawled across the canvas: “Chicago, we own it!”

Sometimes, in lieu of or in addition to her signature, she’d embellish her paintings with real pieces of cheap jewelry or a photobooth picture of herself holding the very same painting she was selling. To save on tools, she was known to remove the piece of jewelry before handing over the just-purchased painting to the buyer. Sometimes she also made cheaper duplicates of her work, selling the more vibrant versions at a higher price and the lesser ones to art students (who may have not appreciated the bait and switch) at a mark-down.

In this age of Instagram and photo filters, however, Godie’s most relevant work may be her selfies—black and white photos she took of herself in the Greyhound bus station photobooth. In these, she experimented with poses and facial expressions, sometimes bizarre makeup and styling choices (she liked using iced tea powder to make herself look tan), and artistic identities (posing with her tools of the trade or paintings). Often she colorized her selfies to make her lips or cheeks look ingenue pink or movie star red. Most importantly, despite her gray hair and secondhand clothes, she defied age expectations and ageist beauty standards in glamour girl poses, showing her bare shoulders or pouting her lips like a starlet.

By the 1980s, Godie had attracted national attention in articles about her in People and the Wall Street Journal. The articles led a woman named Bonnie Blank, her long-lost daughter, now a middle-aged woman, to track her down. After shadowing her mother for a while on the streets and sharing her company while drawing in the park, she revealed who she was. Godie didn’t miss a beat: “Yeah I know who you are, now pick up those bags and let’s get down the street.”

Godie’s daughter became her guardian and finally got her off the streets. In the fall of 1991, Chicago celebrated “Lee Godie Exhibition Month” by decree of Mayor Daley, and in 1993 the Chicago Cultural Center hosted a major retrospective of her work. She died in March 1994, in her mid-80s. Since then, her work has shown in Paris and London and is collected in the Smithsonian in Washington, DC and in the American Folk Art Museum in New York. Sadly, her groundbreaking, anti-ageist selfies are not included in either collection.

Connections: As mentioned above, I recently published an essay about aging and menopause at Poetry Potluck, a series of essays about food and poetry by the University of Tucson’s Poetry Center. I wrote about the fabulous poet Dimitra Xidous’ poem “Raisins” from her Keeping Bees collection—and there’s a recipe for bread pudding! If you’ve never read Xidous’ work, do yourself a favor and check it out. Here is a video of her reading another of her poems.

My favorite book collection of Vivian Maier’s work is Out of the Shadows by Richard Cahan and Michael Williams. The text is thoughtful and illuminating, and the photos are organized in a beautiful, poignant arc that does justice to Maier’s long and productive artistic life.

My favorite essays about Lee Godie include Nadine Modem’s in Elephant and Joe Lamb’s account of his friendship with her while attending SAIC.

Speaking of SAIC…after a year off due to the pandemic, the Met Gala in New York returned, compete with (maskless) celebrities and at least one (maskless) U.S. representative wearing a dress that got nobody talking about the arts and arts workers. Well, here in Chicago—whose radical laborers basically gave the country Labor Day—arts workers and museum/school staff from the Art Institute and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago have been marching to form a union. (With their masks on! AOC, take some notes.) As a former SAIC employee, I can attest that this union is sorely needed. Here’s a petition where you can support them. You know Lee and Vivian would.