How did you spend lockdown? Were you alone the entire time or with family, friends, or roommates? Did you nearly lose your mind from the isolation or close quarters?

How did you cope? Did you throw yourself into any long-neglected hobbies, finish any previously half-hearted projects? How did that go? What did you learn about yourself, about creativity and isolation? About loneliness, its dark energy, and what it brings to the world?

I wonder, when we’re all past the COVID era, how many artists and creators the isolation of the pandemic will have made of us all. Of course, not everyone had time to dabble in homemade tortilla making or sonnet writing during lockdown. The pandemic exposed all sorts of inequities in leisure time, quiet, personal space, work, family, & home arrangements, support (emotional, physical, financial), and access to the technology necessary these days for more and more activities (even unrelated to employment) and human connection. You can fall down an internet rabbit hole of essays, articles, studies, and think pieces about these inequities and the resentments they’re fostering between people of all different lifestyles, experiences, and circumstances. The truth is, we’re all stressed and hanging on.

I know I am. Personally, I was able to work from home for most of 2020, with the help of a cheap laptop and basic internet service. I live alone, so I had plenty of space and quiet time to myself. I tried to make the most of it. I began a yoga routine. That didn’t last long. I started going for long walks in a nearby woods, developing a habit of going there to count how many deer I spotted. That was easier to stick to than yoga. (For the record, the highest count in one walk so far is 13.)

On the flip side, sometimes my job required me to go into the office, to catch up on stuff I couldn’t do from home. Working from home eliminated commute time, but it didn’t necessarily cut down on the time it took to do my work. I felt more stressed than ever. I’m also a caregiver to my elderly parents, who live just a couple miles from me, and of course I couldn’t go to them as often and risk infecting them. Still, there were times I had to break the rules and help them in-person. Even as I looked forward to getting out and going into work at times, I resented having to expose myself on public transit. It felt like a catch 22, like I was putting my parents at risk one way or another, whether by visiting them in person or by neglecting them to quarantine. Quarantining while caregiving proved to be a difficult balancing act.

I worried about my parents, and my siblings and their families, constantly. At night, I had panic attacks and heart palpitations. I had insomnia. As a single person, sure I had plenty of time and space to read, write, watch movies, bake, or fix up my apartment—but I was no more able to focus than the next person.

It’s funny how much guilt ensues from not being more productive even during a global plague. I doubt I’m the only one who felt I failed a test during lockdown, like a test on how to harness your loneliness, how to turn anxiety into a companion that brings out your inner creative. Maybe it’s just good old-fashioned survivor’s guilt—the sense that for every week that you manage to evade COVID, you need to keep proving the worth of your survival, to show something for the time you’re being given when COVID is making it run out for so many other good people.

Before the pandemic, back in 2018, I read The Third Coast by Thomas Dyja, a book about Chicago, my home city, in the 20th century. The book introduced me to a local (and deceased) artist named Henry Darger. Darger isn’t a big part of the book compared to others like writer Nelson Algren or gospel singer Mahalia Jackson—but I was intrigued. After finishing it I made a visit to a gallery in the city, Intuit, which has a collection of Darger’s work, a re-creation of his apartment and work space, and work by other people called “outsider artists.” Something, I don’t remember what, made me think of Darger during lockdown.

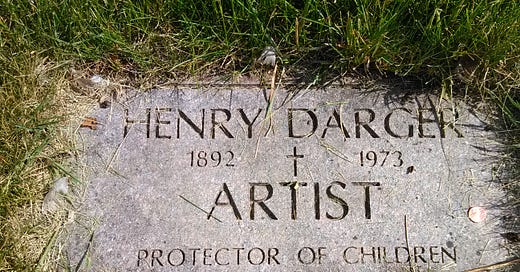

A couple months ago, as the city of Chicago and surrounding Cook County reopened from COVID lockdown, I walked from my apartment to see the grave of Henry Darger in All Saints Cemetery in Des Plaines. I went there because it seemed a good idea to re-emerge from a year of social isolation with a visit to the resting place of the ultimate outsider artist.

The cemetery is a two-mile walk from my place. On foot, it feels like a journey through the neglected soul of Americana. A straight shot up a road that follows the smelly old Des Plaines River, crosses a commuter train tracks, squeezes past a Popeyes and comes close to the site of the world’s first McDonald’s (demolished in 2018, it’s just an empty lot now), then a car wash, a garden center, and assorted strip mall franchises, over a freight train tracks, past a trailer park, a bunch of mausoleum businesses, a massive medical complex, and finally a golf club with a giant pocked white ball at its entrance. After walking a shaggy shoulder of lawn (the sidewalk runs out, of course), there’s a cemetery gate on either side of the road. Darger’s grave is in the older, original cemetery on the east side of the road.

It’s a humble memorial, a flat stone at the back of the grounds in the Old People of the Little Sisters of the Poor plot. When Darger died in 1973, he was living in an old folks home run by the Little Sisters in Lincoln Park, the same place where his father had died in 1908. The sisters supplied a pauper’s grave. Darger had been poor his entire life, institutionalized for much of his childhood, then working as a janitor or dishwasher in a series of Catholic-run hospitals before failing health and ability forced his retirement in his early 70s. The current gravestone came a little later, paid for by Nathan Lerner, an accomplished photographer who was also Darger’s landlord and the man who rescued the poor old man from a certain entirely erased existence. It was Lerner, along with another tenant on hand to clear out Darger’s cramped, dingy, one-room apartment at 851 Webster, who discovered Darger’s lifelong secret.

Most people acquainted with Darger described him as a strange, lonely old man who muttered to himself, avoided people, went to Mass several times a day, and haunted the neighborhood alleys and trash cans collecting junk for…well, who knows what purposes hoarders and collectors pick up junk for. He seemed to have no family, no friends. In truth, he was an artist. A good one too. Good enough for his works to wind up in museums and galleries around the world, fetching up to $1 million, in the years after his death.

Along with massive collections of twine, rubber bands, magazines, and newspapers that Darger had scavenged from Chicago alleys and trash cans over the decades, Lerner discovered in Darger’s apartment hundreds of paintings and collages and a 15,000-page manuscript telling the story of seven young Christian girls leading a rebellion against an evil government that practiced child slavery. Titled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, it’s better known these days as In the Realms of the Unreal.

Many of the paintings illustrated scenes from the epic novel, depicting excessively bloody battles and torture as well as idyllic landscapes filled with fantastical creatures and flowers. The children in these scenes, as in the novel, were predominantly little girls, but with male genitalia. Some paintings showed the same girl child over and over again, the same sweet face, ringlet curls, and static pose of innocence reproduced in a lineup with only varying dress patterns or flower hairclips to differentiate one from the next. Darger’s tools were a small, cheap watercolor set, clippings and torn images from magazines and newspapers, tracing paper, and reproduced images that were sometimes sent out for enlargement in a photo lab.

As far as anyone knows, Darger had no formal art training. Until his landlord and neighbor entered his apartment for clearing out, no one guessed he was an artist. When the neighbor visited Darger at the old folks’ home to ask about the discovery, Henry’s only response was “Too late now.”

Too late now. All evidence suggests Henry Darger created every night of his life, alone in a cramped apartment on junk-scavenged supplies and the very few basic tools he could afford on meager dishwasher’s wages, from around 1910 to just a few years before his death in 1973. His biographers now know he did have one friend in his adulthood—a man named William Schloeder who may have also been his lover. Two of the three photos known to exist of Darger show him with his friend at Riverview, an amusement park in Chicago in Darger’s time. Otherwise, Darger really was a loner. Neighbors could hear voices coming from his room at night—but they were all Henry’s, replaying daytime conversations and arguments with the nuns and such, or maybe just living in a world of his own, in the realms of the unreal.

If you’ve seen any of Darger’s art, you know it’s not to everyone’s taste—which is another way to say some of it is very disturbing, at least confounding. What’s impressive about it is that Darger really did create a world of his own, populated with imaginary beings and events as well as themes that seem to reflect the troubling experiences and anxieties of his own life. Art scholars can show how his work evolved and improved over the years, how he developed techniques—seemingly, ones he figured out for himself through trial and error. (An excellent source for this is Klaus Biesenbach’s 2019 book, Henry Darger.) Darger’s writings express many moments of frustration and anger in his art creation (and in many of his other compulsions, which were legion). Still, he kept at it.

As easy as it is to feel disturbed by some of Darger’s art, it’s also easy to be touched or inspired by his energy, to fantasize about giving yourself over to creating without concern for whether anyone else will ever see or understand your creations. To just work, just create, just disappear into your own world, night after night, error after error, breakthrough after breakthrough.

What made Darger an artist? What or who was he trying to connect to through his art and writing? Was his art just a way to harness the tremendous loneliness and isolation of his life for good—for beauty or entertainment or self-soothing and understanding? Or to justify the supposed emptiness in a life without family or (many) friends, to make some use of himself? Did Darger really have that much more free time and energy than those of us living through the pandemic—a man who labored as a custodian for such low wages he couldn’t even afford a pet, according to the testimony of a neighbor in a documentary about him.

Is loneliness essential to creativity? How much of people’s impulses to take up hobbies and creative projects during lockdown stemmed from loneliness rather than boredom or a mere desire to stay productive? Would there be, can there be, art without loneliness? I think to say no suggests there’s some creative vacuum in human connection, an emotional fulfillment that also results in creative stagnation.

I don’t have the answers to any of the questions I’ve posed here. I’m just another schmo trying to make sense of this strange and scary time we’re suddenly living in and the worries and impulses that the pandemic has brought to the forefront of daily existence, that have made so many previous concerns seem petty, or amplified them like all those inequities we can no longer ignore. I miss people but also feel the need to preserve and safeguard my energy. So many impulses feel in conflict with one another. Being around people when things reopened has been as awkward as it was exciting, like feeling alone in the middle of a crowded party, like living on an island in the middle of a big city.

I decided to start this newsletter to explore people, places, topics, and events related to loneliness, isolation, creativity, singularity, and connection. This includes outsider artists and other interesting misfits, specifically those associated with Chicago, the “Second City,” a great metropolis located in the heart of flyover country, a big city that is consistently overlooked. Which makes all its artists and residents outsiders, and everything that happens or develops here something of an open secret.

The next newsletter will focus more on Henry Darger’s life and how his experiences influenced his art, as well as what his being a Chicagoan means, if anything. After that, I’ll move on to other people, places, and topics: Vivian Maier and Lee Godie, the Chicago Riverwalk and one of its bridgehouses, the Technicolor Man of downtown Chicago, Jean-Baptiste DuSable, Tim Robinson and the Aran Islands, the islands of Chicago (Goose, Northerly, Stony, Blue), learning Irish in America, the sand dunes of Indiana and the boy who fell inside one, Girl X, the Green Mill and Michael Mann’s/James Caan’s Thief, the Pigeon Man of Lincoln Square, informal economies and the vanishing Chicago hot dog vendor.

Connections:

My gratitude to the following sources on Henry Darger. Klaus Biesenbach’s book Henry Darger has great essays by Biesenbach, Michael Bonesteel, Carl Watson, and Brooke Davis Anderson as well as color reproductions of Darger’s art and excerpts from his writing. Bonesteel also has a website about Darger with tons of information, links, images, recollections—it’s terrific. Jim Elledge’s book, Henry Darger, Throwaway Boy, sheds light on Darger’s friendship with William Schloeder. Thomas Dyja’s The Third Coast and Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City both feature chapters and unique insight on Darger. Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art on Milwaukee Ave. in Chicago has a re-creation of Darger’s apartment and gives visitors a chance to see great work by artists (outsider and self-taught) who deserve more attention than they’re given by larger institutions. Jessica Yu’s documentary The Realms of the Unreal is so good—it has interviews with Henry’s former neighbors as well as his landlords, Nathan and Kiyoko Lerner.

No man is an island. So tell your friends!