Stranger to stráinséar: For Tim Robinson

For Tim and Mairéad Robinson, fellow Aran Islands blow-ins

This edition of Island in the City varies from the usual Chicago focus of previous editions. It is called Island in the City, and this time you’re getting the “island” edition. Next edition will see us all back in the city.

Are there expiration dates on memorials? When a favorite writer or artist dies, is it absurd to let a full year and a half pass before writing an appreciation? I’m asking for a friend and a stráinséar (the Irish for stranger”). One and the same person, someone I knew about a quarter of a century ago.

I think the answers to those two questions are no and yes. No, there’s no expiration date on memorials. And yes, of course it’s absurd. But only because time as humans think of it is absurd. Something most of us embody for just a few years on Earth—adding up to maybe one pulse in the universe’s eternal heartbeat—and yet try to impose on random objects and complex processes with arbitrary expiration dates? Even the acknowledgment of loss and appreciation through tribute and memory? Ridiculous.

So here’s a memorial no more overdue than a memory from 25 years ago or a story that began 25 centuries before that, on a land formation born maybe 250,000 centuries (but likely more) before that.

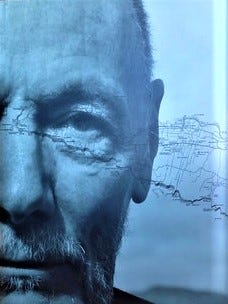

In April 2020, the writer, mapmaker, mathematician, and artist Tim Robinson died from coronavirus. He was 85 and had outlived his wife, Mairéad, by just two weeks, after she too died from the virus.

Robinson, an Englishman who moved to Ireland in 1972 to live on the Aran Islands off the west coast of the country, isn’t as well-known States side as he should be, even among American Hibernophiles and lovers of Irish lit. Maybe his subject matter is too local, or maybe it’s too vast. Likely both.

Robinson’s first books took on a plot of Irish land 12 square miles in total—barely more than half the size of the island of Manhattan—and a history in the making for a cool 10 or 15 thousand million years. With so much time yet so little space, he was able to give his subject the epic treatment, as if those twelve square miles were the epicenter of the Earth. To read his work is to feel utterly dwarfed, humbled, amused, and awed by this small bit of land and the way a human population has changed and been changed by it.

Robinson had his own varied history. He started out as a mathematics and physics student at Cambridge in the late ‘50s. Soon after graduation he met Mairéad Fitzgibbon, another recent graduate and an Irish-born activist and arts worker, in London. They married, and for the next decade Robinson worked as a visual artist and teacher in London, Vienna, and Istanbul. When Mairéad saw a brooding, elemental “documentary” about the Aran Islands in Ireland, Robert Flaherty’s famous and infamous 1934 classic Man of Aran, she and Robinson made a trip to the islands in the summer of 1972. By November that year, they’d moved there.

Robinson and Mairéad—known as “M” in Robinson’s books—settled on the largest of the three Aran Islands, Inis Mór. They began learning Irish, the first language of the islands, and taking long walks around the island. Robinson spoke with the locals, collected place names and their meanings and stories from the old islanders, and began creating exceptionally detailed hand-drawn maps of the islands. These he would eventually publish along with similarly intricate maps of the Burren and Connemara (on the Irish mainland). He and Mairéad would found an imprint for publishing the maps, Folding Landscapes, out of a former lace factory in the fishing village of Roundstone in County Galway, where they moved in 1984.

Two years after moving to Roundstone, Robinson published Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage. The book’s subject was Inis Mór. Specifically, the perimeter of the island. It begins with Robinson standing thigh-deep in the ocean, contemplating time going back thousands of millions of years and intently watching the waves roll in and out. Until he realizes two of those waves are actually dolphins, leaping through the water in perfect harmony with each other and the waves.

“They were wave made flesh, with minds solely to ensure the moment-by-moment reintegration of body and world.”

This “wholeness beyond happiness” makes Robinson despondent even as he feels wonder. Is there a human equivalent? A “good step” like the dolphin’s “wave made flesh”? Robinson vows to make a pilgrimage around the island—in step, but also in time, through language and history, through culture and customs, through folklore and flora and fauna, through geology, through the science and stories of stones and air and sea.

Starting at the island’s eastern end and following the way of the sun, Robinson walks the perimeter of Inis Mór, remarking on particular features of the landscape as he goes—a jumble of stones, beds of seaweed and fossil shells, a storm beach, a puffing hole, an ancient stone fort that abruptly stops at a cliff edge 300 feet above the sea. Nothing is too lowly or insignificant for a story. How this field got its name. How this rock from over there ended up way over here. How one saint drove off another. The many island names, variants, and purposes of seaweed. The differences between limestone and granite, and how they led to a crude nickname for the Aran islanders by Connemara people across the bay and an equally judgmental one for Connemara people by the islanders.

In one stretch of shore, in a chapter called “Signatures,” Robinson tells about an ephemeral art installation that fell to misfortune after one of the west coast’s many storms and a nearby not-so-ephemeral sprinkling of fossils formed by the spore of an unusual alga. Also close by is a series of faint “horseshoe-shaped ripple-marks in the bed of a rivulet worn by rainwater in a sheet of bare rock.” So what, right? Well, according to island legend, these are no random timeworn landscape marks but sea-horse marks—“sea-horse” as in capall fharraige, or stail fharraige (“sea stallion”). Or rather, its foal, going by the faintness of the marks and a few key sightings of the creature by long-gone islanders whose stories among the current generation, as Robinson puts it, “are not disbelieved.”

Not all the stories are so charming or sentimental. There are stories about famine and poverty, about feuds, about drownings, about deaths by cliff fall. In “History of a Stranger,” Robinson tells about an Englishwoman who lived on the island in the 1930s, the artist Elizabeth Rivers. Rivers wrote a gentle memoir of her life there, Stranger in Aran, in which she left out one of the crueler experiences she endured, as well as a stark example of Irish Catholic misogyny. Unlike the custom among islandwomen and many Irishwomen on the mainland, Rivers wore trousers. It made her a target for the island priest, who drew upon Old Testament scripture in a sermon to indirectly encourage the local children to throw stones at such “immoral women” as the kind who wore men’s clothing.

When Robinson got done with the perimeter, he moved to pacing the island’s interior, publishing Stones of Aran: Labyrinth in 1995. A thicker text, this one allows a little more intrusion by the modern era, with stories about tourism and 20th-century visitors’ obsessions with a non-existent “pure” Irish stock and nostalgia for a never-existed mystical Celtic-Christian past. There are also a few paragraphs about a 1970s tofu-munching “California man-eater” intent on having an affair with an uninterested islander that I’ll just say ring a loud bell for 1990s island life as well. (Didn’t I say from the start I was “asking for a friend”?)

Eventually, Robinson wrote a trilogy of equally extraordinary books about Connemara. His work gained the praise of the likes of novelist Colm Tóibín and nature writer Robert Macfarlane—better-known writers (at least in the U.S.) who know brilliance when they see it.

Not that this needs saying, but I’m no Colm Tóibín. So maybe my appreciation doesn’t count for much. But Stones of Aran, especially Pilgrimage, changed my life. You might say Robinson’s books are the ones I’d take to a desert island. Even if I did already read them on an island. An island very much like the one the books are about.

The year Labyrinth was published I landed on Inis Oírr, the smallest of the Aran Islands, meaning Inis Mór’s “sister.” I’ve written elsewhere, a lot, about my coming to Inis Oírr and my life there, and I don’t want this newsletter to be a rehash of any of those writings. So here’s the short version…

When I was 22, I was a cooking school student who heard about a work abroad program for students. I signed up and got a permit to work in Ireland. I went over in May 1995, didn’t know a soul, had no job pre-arranged, nowhere to live, not even a credit card to my name, and went from Dublin to Galway on the west coast, living out of a scuzzy junkie hostel (and I mean junkie in every sense of the word) overlooking a canal (that I once saw a dead body floating in) while looking for work.

Ireland was still just on the cusp of the Celtic Tiger and I was having no luck with even the most basic jobs. So I blockaded myself in a phone booth in the middle of Eyre Square (yes, this was a pre-internet, social media, and cell phones time—and yes, it was fabulous, I’d love to go back) and called down a list of hotels out of the phone book. One of the hotels answered in a foreign language and laughed at me when I asked them to speak English. They took my name and number, just to be nice, and that was that…so I thought. A few days later the person at the hotel rang for me at the dirtbag hostel and said they needed help after all. Only then did I realize this was for a job on some island. Not even Inis Mór, which I had heard of and been to before, but some other one.

The hotel sent its chef on the boat to meet me in Galway and explain the job and island life, and I sat with him in a pub for an hour not understanding a word he said. Just nodding whenever he paused. After another couple days I took a cattle boat out to this island, Inis Oírr, and started work in a small, family-run hotel.

I spent the next three summers working in Ireland, mostly on Inis Oírr, and again in 2001. Inis Oírr is only about 3 square miles to Inis Mór’s 12. At the time, there were about 300 people, three pubs, a small shop, a little cafe and a restaurant, a craft shop, a castle ruin and shipwreck, a lighthouse, and a video store that was really six or eight rotating videos that one family set out on a table in their living room and rented out to neighbors who dropped in. That was about it.

Still, the island stunned me. I spent the first few days walking around in shock, feeling like I was in a dream. The front door to the house I stayed in nearly opened right onto the beach—one that overlooked Galway Bay with Galway City, the Burren, and the Cliffs of Moher beyond. On sunny days, which was often that first summer, the sea was blue as the Caribbean. Donkeys and sheep roamed the island’s little paths. At night, the sky was like a fireworks concert of stars and the islanders would sometimes gather in the pubs and play music, sing sean-nós songs, dance a few steps. In the evening, right in the middle of the dinner rush, the bodhran player would waltz into the chaos to heat up the skin on his drum over the stove’s gas flame, push aside the dinner pots and everything.

No one locked their doors. Everyone spoke Irish. Everyone knew each other. Everyone knew everything that went on.

As someone born in Chicago, raised in the suburbs, thousands of miles from any ocean, of course I was spellbound by this place. And so out of place.

I had no sense of what “small town” life was like, how everyone seemed to know every move you made, that you couldn’t speak openly about whatever was on your mind without it possibly coming back to you in a backtwisted bit of gossip. And as beautiful as the surroundings were, they were also so unfamiliar. I nearly gagged and blinded myself with salt the first time I took a swim in the bay. I had only ever swum in freshwater before. I accidentally swallowed water as I swam—never ideal, but not as much of an issue in, say, Lake Michigan—stood up and sputtered it out of my mouth, instinctively brought my hands up to wipe it away and rub my eyes, only rubbing more salt in.

Language differences. Not just Irish versus English, but Hiberno-English versus Americanese. Cultural misunderstandings. Impossible expectations of what American girls were supposed to know and act like and be like based on the Hollywood make-believe of TV shows and movies. The fact that I was entirely alone, at first, in this part of the world. I had no grip, such very little familiarity to help me gain my bearings.

Over time, I absorbed some Irish, tried teaching it to myself, made my own daily pilgrimages around the island. I’d ask questions about the flowers and stone walls and types of birds and such—but I think my questions only flustered the islanders. Maybe they mistook my attempts to make sense of what were unfamiliar surroundings to me as quizzes of a sort, or as being nosy. Most likely they only had so much patience for the endless questions posed by visitors year in and year out, as I’d start to experience myself.

Meanwhile. Tim Robinson’s books were laying around—in bookstores in Galway, in the island craft shop, occasionally beside a tourist sitting at the hotel bar.

The first couple times I tried reading Stones of Aran it didn’t take. I had no focus the first year or so I was on the island. Even when it got boring, like on dreary days or when more than a couple weeks passed before a visit to the mainland, I couldn’t make the boredom work for me. I was homesick. Boy crazy (I was 22, people). Lonely. Restless. Always bolting down one of the island boreens to the back of the island in between work shifts like one day I’d find a mall or movie theater or some other mundane diversion back there. Or to the end of the beach with one of the other hotel girls to sit on the rocks and talk about how slow the time seems to pass “out here” and what do you think the weather will be like tomorrow and is that a dolphin out there among the waves or…?

I can’t remember when or where or why I finally took to Robinson. I guess one day I finally grew focused enough or bored enough or disappointed with the islandmen enough that when I opened Pilgrimage again and encountered:

“Cosmologists now say that Time began ten or fifteen thousand million years ago…”

I was ready.

By the time I finished the book, the islands looked a less alien place. The landscape, and the culture built upon it and language formed by it, made a little more sense.

It wasn’t that Robinson’s book had all the answers. It wasn’t a primer. It wasn’t meant to be exhaustive, like an encyclopedia of island life. And even then, as young as I was, I recognized great disparities between Robinson’s experience and mine: different islands for one, not to mention that small, traditional, religious communities do not…well, react to the presence of a cultured, married man in his late 30s in the same way they do to that of a solo, single, inexperienced, working-class 22-year-old girl. Robinson himself recognized as much in his stories about Elizabeth Rivers or the “California man-eater.”

I think instead what Robinson’s writing did for me was teach me to focus, to pay attention to details, to see the layers of time and humanity in a place, any place at all, and to connect the dots between even the smallest natural detail, a local word, and a story.

Robinson’s writing is meditative, meandering, wise, sometimes intimidatingly and bewilderingly inclusive of the scientifically complex, and all gloriously pre-internet. It’s not to do with length. Some stories/chapters amount to just a page or two. It’s the layers in each one. The levels of attention and meaning, immense conceptions of time, and epic treatment of an endangered language and marginalized local culture. Robinson expects someone to care. He writes about a long-dead farmer’s half-rubbled field at the back of an obscure island the way other authors write about one of the major battles of World War II or some dust-up between today’s social media titans. It’s like Robinson read Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh’s poem “Epic”—with its lines about “important places” and “great events” like “who owned / That half a rood of rock, a no-man’s land” and “I made the Iliad from such / A local row”—and took it as his personal storyteller’s manifesto.

This may sound like a lot of pretentious conceit, but here’s the thing. Growing up in the suburbs, in the American Midwest, I came to think of nature and the land as remote from me. I was a product of a plastic, superficial culture, a sterile, soulless place. So I believed. I carried that notion with me to Ireland, to Inis Oírr. And it proved to be as much a hurdle to my connecting to my new surroundings as differences in language or history. Think about it. Studies show that if you tell girls they can’t “do science” as well as boys, many girls will believe it and give up before they begin. The same trick goes for all kinds of stereotypes, all kinds of missed connections built on misconceptions.

But sometime after reading Stones of Aran and starting to look at the island landscape in a different way, I started to view my home landscape differently too. And even to read differently. If there were layers of history and meaning in an island field or a fossil, why couldn’t there be in any place or feature? In the kind of weeds that grow between the cracks in a onetime prairie-turned-suburban parking lot, in the disappearance of crows from northern Illinois, in the occasional diagonal disruption in Chicago’s otherwise almost rigidly reliable grid system, in the ever-changing businesses of a single storefront? Robinson’s writing led me to other “nature writers” like Annie Dillard, Gary Snyder, and Wendell Berry, sure. And to environmental books by William Cronon, Terry Tempest Williams, and Mike Tidwell. And to Nelson Algren and Rebecca Solnit. To specific passages in Richard Wright and Edna O’Brien and Colm Tóibín. To writers who didn’t write about nature or the environment—not necessarily, or not at all.

But look, it wasn’t all culture and enlightenment. I mean early on in my Robinson fanhood, I tragically if not entirely regretfully fell in love with an islandman whose seduction tactics included telling me he’d met Robinson after I raved a little too long about Stones of Aran. I was 27 by then. So no excuses this time.

As a reader and human, what Tim Robinson did was give me some bearings, some “Earth legs.” That’s in the long run. Some twenty-five years ago, what he did was give me some “island legs.”

It’s like this: One morning one summer I took the ferry to Galway for the day, and coming back in the evening, the sea had turned rough. Feeling sick, I sat huddled inside the lower cabin until one of the crew, an old Waterford gentleman named John Allen, told me I’d feel better on deck in the fresh air. But standing out there, I couldn’t keep my balance and clung to a pole. The captain, a glamorous English gentleman named Sean, said it was time I found my sea legs. He had me stand in the center of the deck while he, John Allen, and another crewmate surrounded me. They told me to bend my knees a bit, find my center same as on a bicycle, focus on steady point, breathe in the sea air. The sea swelled, the ferry rocked. Every time I fell off balance, which was often at first, one of the men would catch me and push me gently back to the center. This went on about 10 minutes. They were clearly enjoying themselves. It was as funny and ridiculous and wise as it sounds. It took me awhile, but I got the hang of it—and never forgot it. I took the lesson back home with me to Chicago. It comes in handy riding the el from time to time. One “good step” will steady your journey, any time, any place.

Rest in peace, Tim and Mairéad. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a n-anamacha uaisle.

Connections: I could leave a million links related to the islands for this one, but here’s one for each of the Aran Islands. I discovered the blog Doireann in America not long ago, by an Irishwoman who started it when she was living in Chicago. And now she’s living on the middle of the Aran Islands, Inis Meáin. I love her photos and observations of both Chicago life and island life.

On Inis Oírr, islander and photographer Cormac Coyne has been documenting island life for years and has exhibited his work on the island and online. Cormac moved to the island from Dublin about 15 years ago with his wife, Máire, a native islander. You can see some of his photos on Instagram. They are really special for a more intimate view on island life and worth checking out even if you’ve never been to the islands.

Here is a recent video of sean-nós singer Treasa Ní Mhiolláin of Inis Mór singing, with shots of her home island. At the end of this post is another video with an older recording of Treasa singing “Cúirt Bhaile Nua” and images from Robert Flaherty’s film Man of Aran, the docu-drama that inspired Mairéad and Tim Robinson’s fateful trip to the Aran Islands in 1972.

The best Tim Robinson pieces are his books. Go find one and read it. His maps are works of art too. Here’s an interview with him I found interesting, especially his comments about walking versus cycling versus riding in vehicles. The filmmaker Pat Collins made a documentary about Robinson that I have yet to fully see, but there’s an excerpt available on Vimeo. A friend of Mairéad Robinson’s wrote this tribute to her in The Guardian after her death in April 2020.