Who's the real thief?

Losing time, streaming while social distancing, and watching Michael Mann's Thief mid-COVID

Good live entertainment has been hard to come by the past couple years. Streaming’s just not the same. And outdoors only works if you live somewhere the sun always shines.

I’m an introvert and even I’ve missed the in-person energy of seeing or hearing or doing something with a crowd of any size in a shared space. A small nightclub, a big stadium, a mid-sized mall movie theater, a neighborhood tavern, a cafe or library with an open mic night, an art gallery or community playhouse. Any space, as long it’s in the real world.

A few weekends ago I saw my first movie in a theater in gosh-I-don’t-even-know-how-long. It was at a small theater in Wicker Park on a biggish screen. These days people probably have home screens even bigger stuck to their living room wall. Still, it was a special experience.

The film was made by the brother of a friend (link at the end of post) and was part of a group of short films made by Irish and Irish American filmmakers for the Chicago Irish Film Festival. After the screening we all had a chat with a few of the filmmakers and Uber-moseyed to a famous haunted pub right across the street from another small theater where a notorious gangster met his end. Adventures like this used to be all in a night’s work in Chicago.

At the pub, I met the festival’s director and founder. She talked about how film festivals have changed and how important it is to return to in-person screenings, rather than hand it all over to the internet now. The festival had a virtual option following the initial in-person events. Smart move. But still, I agreed with her. Some films, maybe even all films, are meant to be seen on a big screen. Movies with shots of wide natural vistas and lush, colorful scenery. Stuff with special effects or elaborate sets. Or detailed, painstaking costuming that gets lost and goes unappreciated when viewed on a smaller screen. Comedies. Laughter is contagious after all, and those little half-chuckles you make at home watching Bowfinger or There’s Something About Mary aren’t quite as liberating as the loud belly laughs you find yourself making along with the crowd in a theater.

There was a time when you had almost no choice in the matter if you wanted to enjoy some art or entertainment. You had to be there, as the saying went. Except you really did have to be there.

I belong to Gen X, the transitional generation between analog and digital life. Most people in my generation have a pretty even split of memories before the internet and life after everything went digital. For the sake of this post, you can call it a split between the film festival experience and the binge-streaming experience. Even pre-pandemic, I’ve binge-watched at home with the best of them, but I can just as well recall the days when Chicago had only one or two theaters that showed art films, foreign films, revivals, restored prints, and the like. The days when you had to wait forever for that one or two-week window when an art film came to your city, then hustle across town to the solitary place showing it, before it was gone forever. But if the film was good, you’d remember it for a long time to come. It was an ephemeral and yet lasting experience.

Even when TV, cable, and home video became a thing, one after another, there was no guarantee your local video store or library would stock the more indie or arty stuff, or that a TV station would ever air it. Now there’s the internet and streaming and movies on-demand, and you can find (almost) anything with the click of a button on your phone or computer or home screen (almost) anywhere (almost) anytime.

It’s great to be able to watch so many shows and movies without leaving your home whenever you want. Same goes for listening to music. And yet…

Streaming hasn’t cheapened art and good entertainment, no more than did TV or radio or any earlier form of in-home entertainment. If anything, with the pandemic, streaming has just made it painfully clear what we’ve been missing these past couple of years—why going out is such a hyped and hopeful experience, and why entertainment and social venues are truly magical spaces. It’s not just the venues that look better after two years of limited to none socializing. Pre-pandemic art and entertainment also look different. Scenes of emotional connection and touch in older films, scenes of crowds and gatherings, scenes of separation too, they all seem poignant and coded now, like hidden messages that were just waiting for today’s pandemic-weary audiences to see and read them for the depth of emotion and tenderness they really convey.

A great example, IMO, is Thief.

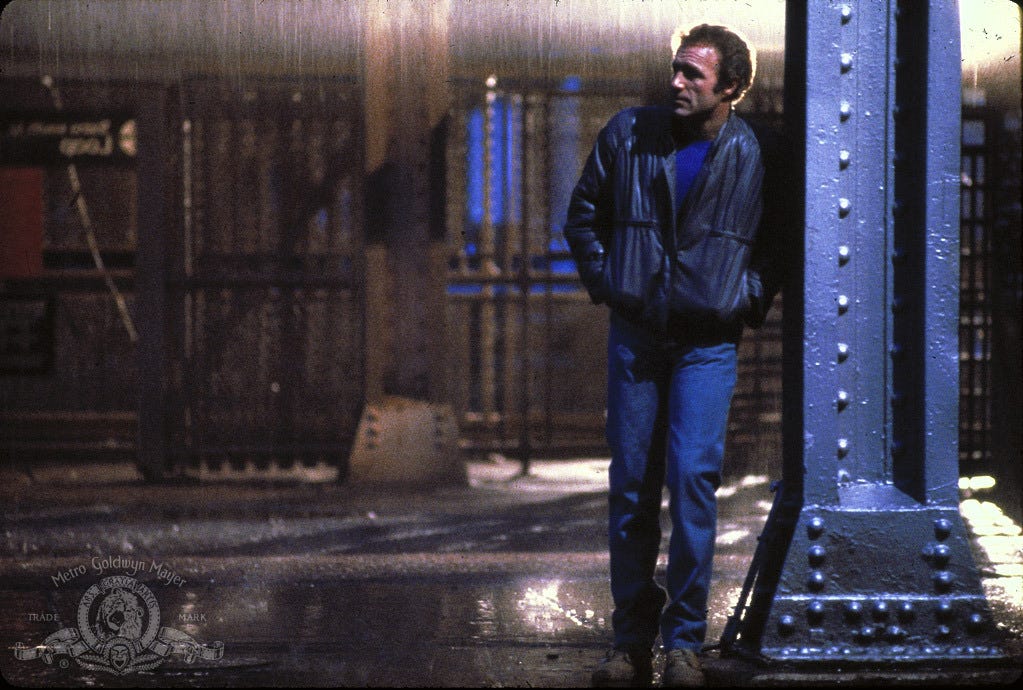

Thief came out in 1981. An underworld story of a thief who tries to cash in on one last big score before getting out altogether—but the local mob has other ideas. The setting is Chicago, the director is Michael Mann, and the stars are James Caan and Tuesday Weld. There’s also total newbies at the time Robert Prosky, Jim Belushi, William Petersen, and Dennis Farina. And most surprisingly, Willie Nelson.

Mann was a newbie too. He had directed TV, but Thief was his first feature film. Upon release, it was critically acclaimed but mostly ignored by audiences. Mann went on to create Miami Vice (both the iconic 80s TV show and the more muted big screen version released in 2006) and direct the films Manhunter, Heat, The Insider, Last of the Mohicans, and Ali. Those projects got a lot more acclaim and attention. But in recent years, audiences have found their way back to Thief.

An overlooked feature of the film is its characters’ relationship to time and its cast’s age range. It is significant that almost the entire cast are people middle-aged and older.

In 1981, Caan was 40 years old, a major star whose career was slowing down. After Thief, he’d go into semi-retirement, struggle with addiction and the death of his sister, until coming back almost ten years on in Misery. Weld, a teen screen queen in the 1960s, was in her late 30s. In the film, she’s still gorgeous, but in real life she was at the age when most actresses are already getting cast as grandmas or can’t land a role to save their life.

Prosky, who plays the local mob boss, was 50 at the time, with just a few minor TV and stage credits to his name. His great character actor career (Hill Street Blues, Broadcast News, Mrs. Doubtfire) was still ahead of him. In Thief he delivers one of the most brutal monologues you ever heard. The combination of authority, menace, and cunning he brings to his performance is palpable. Farina was almost 40 and fresh off nearly 20 years working as a Chicago cop. He was originally hired as a consultant on set, but Mann, a Chicago native himself, clearly recognized a perfect blue-collar Chicago face when he saw one and gave him a bit role as Prosky’s henchman. Farina never went back to his police job. After Thief, Mann cast him in the TV show Crime Story, which turned him into the star he deserved to be.

Petersen and Belushi were both in their late 20s, but if you said Belushi was 10 or 15 years older, people would believe you. Playing James Caan’s burglary partner, Belushi may be the most Chicago thing ever caught onscreen in a scene where he unironically wears a three-quarter sleeve Hawaiian floral print shirt and a magnificently unelegant gold medallion and watch on a burglary scouting trip to California. I’ll get to Willie Nelson in a moment.

Part of the reappreciation of Thief may be simple chronology, the passing of time. Last year marked the film’s 40th anniversary. In normal times, this would’ve meant in-person retrospectives around the country and locally at places like the Gene Siskel Film Center. Mann, Caan, and Weld et al may have even made it out to a screening and film talk somewhere. Because of COVID, the best we got was a bunch of culture websites rolling out their think pieces about the film’s greatness and Mann’s career. Yay internet?

I watched Thief twice during the pandemic, first on a rickety old DVD and the second time streaming. OK, yay internet. But the minute it plays in a real theater again, I’m there.

Still, the pandemic might have been the perfect time of all to watch Thief. At first glance, Thief looks like just another gritty heist movie, complete with cops, mobsters, and big city corruption. There are scenes of violence and brutality (its working title was Violent Streets), plus a courtroom bribery scene that competes with a blues bar scene for being the second most Chicago thing about this movie after Belushi’s wardrobe.

But Thief also captures a vanishing, authentically working class, pre-hipster-and-tourist-oriented Chicago. A city of rainy streets and neon-lit car lots. Faux-wood-paneled suburban basements and standing-room-only blues bars. Skeleton-like vertical lift bridges and alley fire escapes. Shadowy underpasses and shady people. Nondescript red brick business fronts masking mob activity and beige-toned offices masking the corruption and coldness of bureaucracy. And humble heart to heart conversations—one in a prison visiting room and one in a highway oasis coffee shop. The emotions and themes underlying the film aren’t just violence and cruelty, but regret, an aching need for human connection, and the main character’s desperate hope to make up for lost time.

Caan plays Frank, a thief and ex-con whose fronts include a car dealership and a bar. Chicagoans will recognize the Western Ave. location of the car lot. They’ll likely blink hard when they see the Uptown location of his bar. Frank, it turns out, owns the legendary Green Mill jazz club.

Frank is also sweet on a stunning Lincoln Ave. diner cashier named Jessie, played by Weld. His idea of courting her is to say hi to her every morning at the diner for half a year before finally asking her out, then standing her up at the Wise Fools Pub before aggressively driving her over to the former Howard Johnson’s in the overpass oasis out on I-90 for a long, meaningful conversation. (This would have been a bit of a drive in real life, but no one outside Chicago knows the difference and the scene is so effective so…) On the way over he shouts lines at her like, “So let’s cut the mini-moves and the bullshit and get on with this big romance.” What gal could resist?

Seriously, this ten-minute heart-to-heart diner scene sets Thief apart from most heist movies and lays out Frank’s deepest emotions (link at top of the post). It may be the film’s most memorable scene, because it’s both beautifully written and played and so unexpected in a film like this. Sitting a few inches across from each other at a window dinette, Jessie and Frank spill their life stories. The camera keeps the headlights from the cars speeding beneath the overpass in the frame at all times, and the conversation is punctuated by the sound of the cars rushing along. A good noir effect, but also a reminder of time swiftly passing no matter what two people sitting in a diner may be doing.

As Jessie and Frank talk, we learn Jessie has a sad, shady past of her own and Frank barely escaped murder or worse while losing 11 years of time in the joint for the initial crime of stealing $40. Jessie expresses unconvincing gratitude for the ordinary, boring routine her life has become, but Frank sees right through it: “You’re marking time is what you are…You’re waiting for a bus you hope never comes because you don’t want to get on it anyway because you don’t wanna go anywhere.” Jessie bristles against Frank’s approach at first but softens as she hears his story. It says something about her life experience and current options that she ultimately tolerates Frank’s impulsiveness and rough edges.

Earlier in the film we saw Frank having another heart to heart, this time with his mentor, Okla, played by Willie Nelson, through a prison visiting room screen. That scene is played as intimately as possible given the barrier between the two men. Both of them keep eye contact the entire time, even more so than Jessie and Frank in their diner conversation. Okla asks Frank to promise to help get him out of prison sooner than later so he won’t die there (Okla has a heart condition), and Frank tells Okla about his plans to make a life with Jessie, even though Frank hasn’t even had his first date with her. And Okla has yet to get a pardon. But neither man seems to have time for anything but hope.

Time is clearly on Frank’s mind on his date with Jessie. He hands her a collage he made in prison that represents his vision of what life is and what it should be. A home, wife, family. There’s a cut-out of skeletons in one corner. Frank explains. On the inside, “you can’t even die right.” Outside of prison, you grow, you get old, you get married and have children, you’re part of life’s cycle.

“Who’s the old man?” Jessie asks, pointing at a photo of Okla smiling from the upper right-hand corner. In real life Nelson was not even 10 years older than Caan, but he was so grizzled-looking, he could believably play an old convict. Roger Ebert’s original review of Thief named Nelson’s brief screen time as the film’s only flaw. “The Nelson character quickly disappears from the movie, and we’re surprised and a little disappointed.” But that’s the point. We’re experiencing both Frank and Okla’s time crunch through their eyes. Okla’s fleeting freedom and Frank’s loss make us understand the stakes more deeply.

Frank is only supposed to be about 34, but casting an over-40 actor was the correct choice for a guy who “has run out of time,” as Frank tells Jessie when she balks at his proposal to start a life and family with him. “I have lost it all. I can’t work fast enough to catch up. And I can’t run fast enough to catch up.” Jessie tells him she doesn’t fit in with his vision, that she can’t have kids. She offers no details, but the implication, as with Frank, is her options in life are growing more and more limited as time passes.

Frank tells her they can adopt. And his life has been a mess. And he has a way “to make it happen much faster.” All of which sets up the big heist to come and the film’s violent finale. Along the way, Frank has one confrontation after another with various forms of authority, both official and underworld. In heist movies we expect scenes like this with cops and mobsters. What we don’t expect is a painful confrontation with an adoption agency that pits Frank’s messy life experience, of a formerly incarcerated person who was “state-raised,” against the kind of cold, classist, surface-orderly bureaucracy that shuts people like him and Okla away to steal years of their life without batting an eye. “This is a dead place,” Frank erupts at the agency clerk. The kind that makes kids wait forgotten in a room just for a chance to be part of a family. “After a while you tell the walls, my life is yours.” Who’s the real thief?

These scenes are touching or heartbreaking on their own. During a pandemic, a time of social isolation, they feel almost coded.

There’s no comparison between spending years of your life behind bars and spending a couple years having to refrain from shopping and moviegoing as much as you’d like. There’s no comparison between being a kid who’s “state-raised” and stuck in a holding place and being a temporarily home-schooled one who’s missing out on prom and graduation ceremonies due to COVID.

The experience of an ailing convict dying in jail just weeks before making a pardon is not equatable to one of someone in a nursing home dying alone and isolated from COVID.

Or maybe it is. Maybe that’s partly what’s been so unsettling about the pandemic. COVID has exposed great disparities in fortune and favor, made plain tremendous inequities that anyone with eyes could’ve and should’ve seen along. Privileges of economics, class, race, education, ability, age. But along with the disparities are disarming similarities. Nobody really uses time—time uses us. We all have an expiration date. And all our hopes and plans and choices are played out against the soundtrack of a ticking clock.

Even with lockdowns lifted in most places, and entertainment venues reopening, public life still seems precarious. There’s a long way to go until normalcy returns—and of course, given the kind of disparities revealed, some people want anything but a return to past normalcy. But if there was one thing returning to, it’s the public place that art and entertainment occupied in our society. Art and entertainment have always been a way to process overwhelming events and traumas. Music heals wounds, dancing invites us to fun and beauty, storytelling allows us to step into the experience of others, and plays and movies give us catharsis. You can experience it all alone in your living room, yeah, but if that becomes the new normal, then it will be clear that COVID has stolen even more from our lives than time.

This post is part one of a two-parter that discusses not only Thief and COVID, but public art and entertainment venues. The next post will continue the conversation about Thief but focus more on its depiction of Chicago nightlife—its clubs, its bars, its music. Especially the legendary Green Mill. I hope you’ll stay tuned.

Connections:

I started this post talking about the Chicago Irish Film Festival. Gordon Hickey is my friend’s brother, a born and bred Dubliner, and a talented up-and-coming filmmaker. Below you can see the trailer for his short film “The Cure,” which showed at the festival. Gordon directed, wrote, and starred in the film, which he made over just a few days’ time mid-pandemic in Dublin. Perfect for the theme of this post, Gordon’s short film is about a man in a race against time—and it’s terrific. Check it out and watch out for more from Gordon in the future.

After Thief, Michael Mann made pop culture history with the TV show Miami Vice, a show that was equally celebrated and mocked for its pastel wardrobes, MTV-style editing and music montages, and two ridiculously handsome male stars, Don Johnson and Phillip Michael Thomas. I remember the show well, though I was still a pre-teen when it debuted, and it was a bit too “adult” for me to watch often. More than just an 80s sensation, Miami Vice was the launching pad for many future stars. Bruce Willis, Jimmy Smits, Liam Neeson, Ben Stiller, Wesley Snipes, Julia Roberts, Helen Bonham Carter, Benicio del Toro, the list goes on and one. The show also often cast already-famous music legends, from Miles Davis and Frank Zappa to Phil Collins and Eartha Kitt. in A couple years ago, someone created an amazing Twitter thread of the many famous faces who got their start or sneaked in a cameo on Miami Vice, starting with Married with Children’s “Al Bundy,” played by another great Chicago actor, Ed O’Neill.

Correction: Turns out O’Neill’s not from Chicago, he’s from Ohio. Where did I get the idea he’s from here? Maybe because Married with Children was set in Chicago. I don’t regret the error, I’m just embarrassed by it.

“Things did happen” is what Jessie tells Frank about her past on their diner date. Thief leaves Jessie’s past and future a mystery, leading some critics to dismiss her character as just another marginalized girlfriend role. A couple years ago filmmaker Julia Hart released I’m Your Woman, which took Tuesday Weld’s Thief character as its inspiration for a story about a woman who has to go into hiding with her baby after her thief husband disappears. The characters’ names are different, the setting is, uh, Pittsburgh instead of Chicago, and the actors in the main roles look about 10 to 15 years younger than those in Thief. The era is also a little earlier, in the 70s—in the trailer there’s a disco shot in place of Thief’s timeless Chicago blues bar. I haven’t seen this film, since you have to pay to stream it, and I’m a cheap woman. So I can’t tell if this version keeps the Jessie-inspired character’s shady, complicated past. But Hart’s idea to follow the woman for a change is fresh and welcome.

If you must stream, and you’ve read this far, Thief is currently available for free on lots of streaming channels like Kanopy and Roku. If you’ve read this far and you own a movie house in Chicago, or know someone who does, consider scheduling a few screenings of Thief in the near future. It’s a beautifully styled and filmed movie, and we all deserve to see this gem on the big screen.